Switzerland is a good place to be reminded of the fact that Europe is more than the European Union. Europe is, of course, a geographic entity that includes countries like Switzerland, Norway and Ukraine. But it is also an economic, political and social model that has been shaped by common historical and cultural experiences. Much of the rest of the world envies and tries to imitate this success. But in Europe itself, doubts are spreading. The euro crisis, for instance, has led to deep divisions within Europe, as has the situation in Ukraine.

“Is Europe Facing Fragmentation?” was the topic of a Young Professionals Seminar that took place in the Swiss mountain resort of Arosa from September 19 to 21, 2014. In the clear, thin air of the high Alps, young professionals from nearly 20 different European nations had gathered to debate how those divisions can be overcome. Each of the 22 participants had prepared a short presentation on some aspect of this topic, allowing for a huge diversity of arguments and viewpoints. The only thing, many said at the end, was that time for discussion was still too short.

But let’s begin with the beginning. In line with the (still very young) tradition of the Young Professionals Seminars, it was a prominent guest speaker who opened the debate. Josef Ackermann, former CEO of Deutsche Bank, focused on the consequences of the Euro crisis in his speech. His conclusion was surprisingly positive. “There was the strong political will to keep Europe and the Eurozone together,” Ackermann said. “No European politician wanted to be remembered as having been responsible for letting Europe collapse. As a consequence, Europe really did a pretty good job.”

Most appreciated from abroad

Ackermann is a Swiss citizen, but that doesn’t keep him from being a passionate European. In Arosa, he was very clear in his belief that Europe needs more, not less integration. “If we are fragmented, we will always have to accept what other powers in the world decide for us,” he said. “That’s not an interesting future. In the end, our freedom is at stake.”

Ackermann called for a constitutional debate to redefine the division of power between national states and the European Union. He also said that Europe needed to capture people’s emotions. “Europe has a flag, but do we have an anthem that we sing? Do we have a European team playing? Only in the Ryder Cup does Europe play against the United States. We need more of that.”

In the first of the young professionals’ contributions, Carmen Staicu, a Romanian living and working in Austria, also raised the issue that Europe lacks a powerful common purpose. While people in other parts of the world mostly held Europe in high esteem, its own citizens did not associate Europe with anything that would inspire them, but thought of it as a regulatory institution.

A shared destiny

The first bloc of contributions was designed to give the participants a taster of the issues to be explored at greater length on the second day of the seminar. Of course, current events played a role, too: the news that the Scots had voted to stay united with England had come out that very day. Andrew Giblin, a young professional from London, gave a comparison of “Scoxit” and “Brexit”, the debate on whether Britain should stay in the EU or leave it. The tour d’horizon continued with Manuel Gonzalez Igual from Spain speaking about the re-emergence of nationalism in Europe. This has taken the shape of separatism, but it is also obvious in the Eurosceptic movements that are spreading in Europe.

Therese Liechtenstein defended her country’s choice to not join the European Union. The EU would have to be far less intrusive on economic and financial matters and far more coherent on foreign policy and defence issues in order for her to want to become a member. Nick Axel, a young American architect, pointed out how important it would be to explain Europe to its citizens in visual terms. As an example, he showed a map of Europe highlighting an energy grid tying together various possible sources of renewable energy.

The mentor of the Young Professionals Seminar is Anthony Ruys, former CEO of Heineken and founding member of United Europe. It was he who originally suggested that United Europe needed to develop a project to draw young people into the debate about Europe’s future. Ruys, a Dutchman, also oversaw the planning of the two seminars that have taken place to date, the first in Amsterdam in April of 2014, and now the one in Arosa. “Our goal is to help restore Europe’s credibility and bring back the belief in our shared destiny,” Ruys said.

Many thanks to the sponsors

On this note, United Europe is already planning three more Young Professionals Seminars for next year. In March of 2015, a workshop in Prague will address the issue of security and solidarity in Europe. In May, a seminar in Madrid will debate the question of “How to brand Europe”. The third seminar will take place in Finland at the end of August and look at the education and skills young Europeans will need. The organisation of the seminars, lies with United Europe’s managing directors – Bettina Vestring for content matters and Christoph Riess for finances and logistics.

But back to Arosa. The first day’s debates concluded with another guest speaker – Domenico Siniscalco, a former Italian finance minister who is now Vice Chairman of Morgan Stanley. In his presentation, he spoke of a turning point. “Either we want less Europe. In that case, we should settle for being a big trading area. Or we want more Europe because of the many problems that can best be dealt with at a European level,” Siniscalco said. Yet the difficulty of reform should not be underestimated, he said, using a memorable image: “Reforming Europe is like changing parts of an airplane in mid-flight. It is an art, but it also requires luck, good will and a sense of European identity.”

Dinner in the Hotel Kulm’s fine dining hall was given over to discussions in smaller groups. The two main sponsors of the Arosa Young Professionals Seminar were PricewaterhouseCoopers and Morgan Stanley – without their generous support United Europe would not have been able to hold this event. Jürgen Grossmann, the founder and treasurer of United Europe, also contributed considerably by hosting the seminar at his hotel in Arosa. Certainly, the warm hospitality of the Kulm did a lot for the success of this event.

Europe and the world

It was Jürgen Grossmann, too, who opened the next day’s discussions. “My message to you is that we should talk about the revitalisation of European ideas,” he said. “There is no other area in the world where you can live as safely and as comfortably as in Europe. Let’s look at the basics that will allow us to continue that way.” Grossmann stressed the necessity of creating growth and of ensuring a common military defence, but he also spoke of the need to respect Europe’s great diversity of cultures.

Wojciech Przybylski was the first of the young professionals to speak on the Saturday morning; he opened the discussion on Europe’s role in the world with an outline that was both provocative and philosophical. Europe, he said, could not afford to pretend that the use of force wasn’t needed at times. Then, it was Peter Felsbach’s turn. This young Austrian spoke about the difficulties of reconciling political and economic interests. While politically, it was certainly necessary to confront Russia’s President Vladimir Putin over Ukraine, economically, sanctions translated into concrete and painful job losses. Mia Pettersson took a more long-term view. Europe, she said, needed to be careful not to alienate the Russia’s young, pro-Western elite.

Norway, Bjørn Rogde said, had voted against joining the EU mostly for economic reasons. But the fact that the EU received the Peace Nobel Prize in 2012 was an incentive to rethink matters as Norwegians were very committed to promoting peace in the world. Raji-Indira Sharma, a German with Indian roots, then made the case for promoting cultural and ethnic diversity. For nations as well as for individual businesses, diversity was becoming an important economic factor, Sharma said.

The consequence of income gaps

What participants criticized most about the Arosa seminar is that there wasn’t enough time for discussion. Some would have wished for a brief moment after each presentation to reflect on the ideas together. While United Europe will take this on board for the next seminar (though time always seems to be at a premium during these events), it is important to note the compliment implied in this criticism: if the short contributions from the participants hadn’t been so very interesting and thought-provoking, no wish for further discussion would have arisen.

Work in Arosa continued with a set of presentations focusing on legal and economic divisions within Europe. Irish tax specialist Anne-Marie O’Meara began with an outline on how damaging it is to Europe that multinational companies can use loopholes to lower their tax payments. Chloé Pueyo Brochard explained from her experience with her own startup in Madrid how difficult it is for companies to grow and realise economies of scale given the differences in language and law between EU countries. Valentina Vinante, an Italian doctor working in Switzerland, spoke about the shocking differences in the quality of public health care between European countries and even between regions within a country.

Jussi Herlin continued the presentations with a reflection the rising income differentials in Europe and relative depravation, asking whether Europe-wide taxes might be necessary to keep the gap from widening further. Caspar van den Berg then looked at the political consequences of income developments: a large part of the Eurosceptic movement in countries like the Netherlands gained its support from the losers of the European single market and of globalisation. Finally, Philip Caune wrapped up this bloc by describing how big Western European companies have set up production facilities in Eastern Europe to take advantage of lower labour costs. This process helps to even out some of the income differentials between Eastern and Western Europe. Yet the lack of qualified personnel in Europa severely limits those gains.

“Do useful things and brand them properly”

Participants then separated out into three working groups to consider ways to overcome the barriers dividing Europe. All three came back with a similar set of proposals: Europe should, participants said, concentrate very specifically on overcoming economic barriers and national protectionism. For instance, it should push forward with an energy union, a digital single market and finding a common position on trade issues. Given the challenges from abroad and the lack of public funds, it also needed to start moving to a European army.

At the same time, progress should be made on creating a European identity, the working groups said. “We need to do concrete, strategic things that are useful, and then we need to brand them properly,” Manuel Gonzalez Igual summed up his group’s discussions. Others also proposed a branding strategy for Europe to make its people aware of their common destiny. EU-wide commercials, sports and education could all contribute to that.

After lunch, it was time for the next guest speaker. PricewaterhouseCoopers’ partner Lutz Roschker picked up on the question whether Europe was more than a single market. Yes, he answered unequivocally. “From the very beginning, the foundation of Europe was based on a combination of territorial expansion and cultural values, such as the ideas of the Age of the Enlightenment, rather than on a mere economic dimension.”

Avoid becoming a prey

Roschker reviewed the EU’s history over the past 60-some years with more and more power being transferred to the European layer affecting almost all areas and aspects of life. “In almost all areas, the EU has a say, but there is a clear gap between powers transferred and legitimation,” he added. “There is a huge lack of telling the European story strategically, of explaining and justifying the calls for a change towards full integration and economic unity.”

Given the global challenges arising for instance from digitalization, robotics, climate change, demographic developments and urbanization, Europe needed to take a big step forward, Roschker said. “United, Europe has sufficient strength to master these big challenges and to be on a level with the super powers USA and China when discussing them. Only in unity can the European States avoid being a prey in the big game of globalisation.”

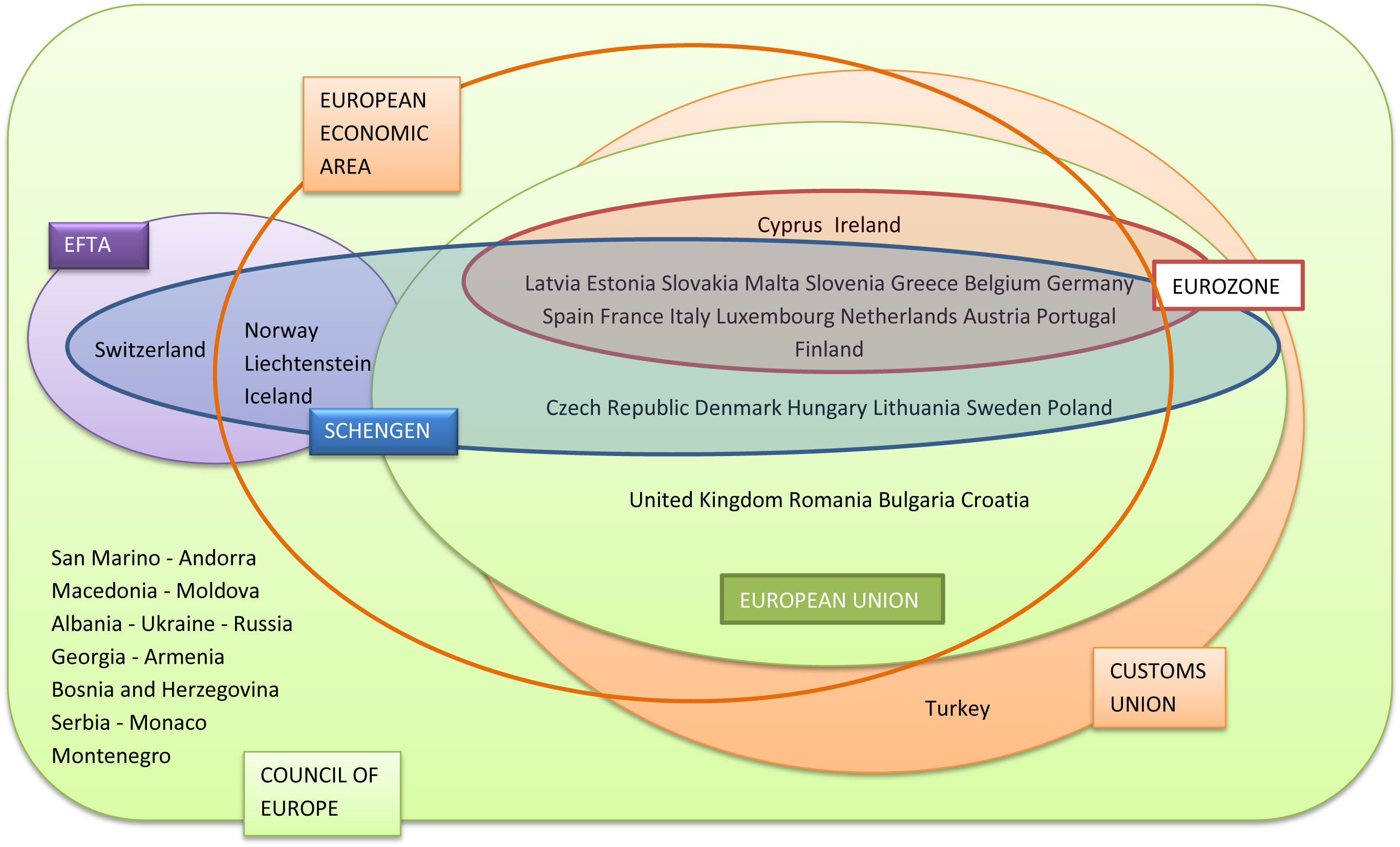

But how can Europe become more united if several of its member states are profoundly opposed to closer integration? It was Monica Tiberi, an Italian member of Europe’s Young Federalists, who addressed this issue as the next guest speaker. Tiberi explained how from the very beginning, Europe had been a multi-speed endeavor. Both the euro crisis and the possibility of Britain leaving the EU were now sharpening the debate.

The fear of being a second class citizen

“The crisis in Europe proves that a monetary union without a central power capable of imposing the necessary economic policies is bound to remain unstable,” Tiberi said. “So we face a crucial decision: either we move forward or we fall back. We either create a real economic and political government to accompany the monetary union, or the euro will continue to be vulnerable, and the euro zone will face the risk of break up.” Tiberi’s proposal was to create a core Europe that has democratic, federal institutions for those who would be willing to join in such an undertaking. The federal core would be joined by an outer ring of countries like Britain and possibly Turkey sharing looser bounds.

Multispeed Europe is a reality

Image by Monica Tiberi

The next participant’s contribution came from Laurence Leclercq, a Brussels lobbyist, who pointed out that there are currently very few platforms allowing for the shaping of a common European public opinion, with media, political parties and economic policies still operating from a national angle. Anthony Zammit explained the British viewpoints on a two-speed Europe that Britain would almost certainly not be part of. At the same time, Zammit made it clear that he is not so sure whether Eurozone countries really are ready to hand over power to a federal Europe.

Enlargement was at the focus of the next presentations. Miroslava Nova spoke about the unease of Eastern Europeans about be turned into a lower cost work force with a lower grade of protection by trade unions. Are the Eastern European countries treated equally, she asked. Janosch Novak spoke of enlargement as an overall success, with the income gap diminishing, security increasing and borders vanishing. Yet a lot still had to be done to overcome stereotypes, he said. In the following contribution, Jan-Philipp Wilckens also stressed the importance of social perceptions. The EU’s success stories should be better promoted, and old member states could help shape perceptions of newer members by entering a partnership with them.

An institutional mess

The final presentation was made by Martina Farkas, a lawyer of partly Bosnian origin, who spoke about the lessons in institution building to be learned from the Bosnian experience. Clearly, institution building will be central to many of the EU’s efforts of stabilising its neighbourhood. Yet the most important conclusion from the Bosnian experience is that such an enormously complicated and largely dysfunctional institutional setup should never be repeated.

Working groups came back from their second and final session with an ironic variation on Bosnia’s institutional mess: in all three working groups, there was a consensus that the institutional make-up of the European Union was nearly as difficult to understand as the one fostered on Bosnia. The way legislative powers, for instance, are shared between the European Commission, the Parliament and the Council is simply baffling to anybody outside the corridors of power in Brussels.

Growth as a lubricant

Add to that a concern over efficiency and transparency of all the European institutions, and there was a clear call for fundamental reform. A majority of participants in the Young Professionals Seminar said they would by far prefer a federal model of government for Europe. And even those who remain skeptical of giving up national sovereignty to a European federation – as for instance one of the British participants – said they would prefer the EU to have a clear institutional set-up even if this meant their own country would end up staying outside.

“But how can we get things started?” Thony Ruys asked at the conclusion of the seminar. Clearly, education would have to change in order to allow more people to understand how and why Europe is working. Bolstering the European identity was also a big task. “But please don’t forget,” Tony concluded. “What we need for any of this to be successful is economic growth. Growth is a very strong lubricant in all the changes you would want to implement.”

Fotos: Christoph Riess