RÉSUMÉ:

On 22 and 23 November 2019 the 17th United Europe Young Professionals Seminar took place in Paris. 22 participants from 15 European countries spent 2 days working intensively on the topic of energy systems transformation and climate change and the strategies Europe is developing to this end. Most of the participants are working for affected companies and the energy sector and already have significant professional knowledge.

The seminar was hosted by United Europe corporate member Enedis, responsible for the management and expansion of 95% of the French electricity distribution network.

The aim of the seminar was to review the current state-of-play of energy policies, four years after the Paris Climate Convention (COP 21), which aims were to limit man-made global warming to well below +2°C compared to pre-industrial levels: What are the objectives of the climate agreement so far, what are companies doing to meet the requirements, what is the situation in the USA, China and Japan?

Keynote speeches and impulses came from Laszlo Varro (Chief Economist International Energy Agency IEA), Joel Couse (Senior Advisor IEA), Prof. Dr. Dr. Dr. h.c. Franz Josef Radermacher (Director Research Institute for Applied Knowledge Processing (FAW/n)), and Carine de Boissezon (Head of Sustainability EDF Group).

In her Political Guidelines for the work of the EU Commission 2019 – 2024, new EU President Ursula von der Leyen has announced that Europe will become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. To this end, it wants to pass a European climate law with the goal of establishing climate neutrality in law by 2050. This is a major undertaking for the new EU Commission in view of the 27 politically, economically and socially completely different nation states. The different starting points of each individual member state must be considered, which is why Poland, which is 80% dependent on coal as an energy source and currently the only member state not having signed up to the goal, is given a little more time (and probably money) to join the measures.

Europe is currently responsible for about 9% of all global greenhouse gas emissions (with a population share of just under 10%). Even if the European decarbonisation targets are achieved by 2050, these efforts will not significantly improve the state of the world’s climate if other regions of the world do not change course as well.

To understand the challenge, the significant increase in global greenhouse gas emissions over the last 20 years is due only to a lesser extent to global population growth, but mainly to the fact that large parts of the population in Asia have risen up to the middle class and are therefore consuming more energy. 90% of all coal-fired power plants built worldwide during this period were built in Asia, and these plants potentially have a service life of up to 50 years.

Achieving the climate targets by 2030 to the desired climate neutrality by 2050 means a tripling in the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in only half the time (compared to 1990).

In individual presentations as well as in the results of the four groups it became clear that climate protection, sustainability, alternative energies and CO2 reduction have meanwhile assumed a key position in most European companies’ strategies. No industry, be it energy, aviation, chemicals or finance, which has not made the issue a priority and is working on solutions to the problem. As the need for sustainable, climate-friendly technology and business models increases worldwide, this also creates opportunities for business and society to support the path to a climate-neutral world by innovation and to stop global warming. In this way, export-oriented industrial companies, research institutions and suppliers can benefit in the medium- and long-term from clever investments in globally growing “climate mitigation markets”.

Prof. Dr. Franz Josef Radermacher explained in a video keynote that the global energy and climate crisis could be solved “in a growth-compatible and wealth-promoting way” by a hydrogen/methanol economy. Three essential elements had to be combined: 1. methanol economy, 2. soils as carbon storage and 3. development promoting CO2 compensation projects. The panic-stricken public debates towards the end of the world, the climate plan economy and the electrification of the entire mobility sector would “in no way do justice to the multi-dimensionality of the challenge”, Radermacher said. His approach would allow Africa, India and other emerging economies to follow China’s path of development without a negative impact on the climate. SDGs could thus also be implemented by 2050.

During the seminar, one of the working groups developed a card game for students that teaches the basics of climate change and its effects in a playful and interactive way. The game divides those responsible for climate change into the categories 1) energy production, 2) mobility, 3) food and 4) material consumption, with the card that represents an activity with low CO2 emissions beating the one with the higher one. Each card also contains brief, detailed explanations.

Whether it will be possible – despite further positive approaches and developments – to achieve the desired climate targets is questionable, however. This is demonstrated not least by the failed world climate conference in Madrid. Every economic actor is responsible for this, not only industry, also each citizen. Carine de Boissezon stressed in her speech that although most people are worried about global warming and in favour of renewable energies, there is little willingness to accept wind turbines or solar plants in their vicinity or even restrictions on their usual lifestyle.

The growing use of the Internet and digitalisation with the associated enormous growth in data traffic and the need for energy-guzzling data centres also pose a major problem for the targeted CO2 reductions. Experts estimate that electricity consumption by WLAN, landlines and mobile phones will increase fivefold from 722 terawatt hours (TWh) to 3,725 TWh per year by 2030. In the meantime, the Internet is expected to generate as many emissions as air traffic, and Bitcoin production consumes more resources than Denmark (German Source).

The group, which dealt with the question of how companies handle energy system transformations and climate change and whether there are positive examples, has revealed another dilemma: many companies now claim to be climate-friendly and CO2-free and to produce sustainably in order to maintain a better image with consumers. On closer inspection, however, this is often not the case because, for example, suppliers to whom certain tasks have been outsourced do not fulfil these requirements.

The transition to climate neutrality requires profound change in all parts of the value creation and economic chain. A far-reaching CO2 reduction can only be achieved through significant electrification of industrial processes, which leads to an enormous increase in low-carbon electricity demand. Therefore, a radical reduction in the price of electricity from renewable energy sources, including government surcharges and levies, is an essential prerequisite for successful industrial change. Ultimately, we need to move towards a low-carbon EU internal market where there is both demand and supply for climate and environmentally friendly products.

To be competitive in a global market, Europe should focus on at least allowing European champions in renewable energy production and clean industrial and chemical processes. In its Green Deal, the EU Commission should therefore examine how collaborative and innovative corporate ecosystems and global European players can be promoted. The assessment of potential barriers arising from consumer-oriented competition law requirements, for example, and how these concerns can be reconciled with the need for a consolidated European response to foreign competition, could also be appropriate points for the European Green Deal.

The final assessment is that the European solution to climate change and energy system transformation must be based on innovation and exemplary solutions while safeguarding competitiveness and jobs, which can also be used by other countries on the road to CO2 reduction and climate neutrality.

DETAILED SUMMARY:

Friday, 22nd November

After a welcome by Sabine Sasse, Managing Director of United Europe, the seminar got kicked-off with a presentation by Dr. Laszlo Varro, the International Energy Agency’s Chief Economist. Laszlo presented the highlights of the IEA’s brand new 2019 World Energy Outlook (WEO), followed by Qs and A’s from the YPS participants.

He explained that the IEA maps three main energy scenarios in its WEO:

1) The Current Policies Scenario that the world is on right now, which provides a baseline picture of how global energy systems would evolve if governments make no changes to their existing policies. In this scenario, energy demand rises by 1.3% a year to 2040, resulting in continued strong growth in energy-related emissions.

2) The Stated Policies Scenario (formerly the New Policies Scenario) which incorporates today’s policy intentions and targets in addition to existing measures. The future outlined in this scenario is still well off track from the aim of a secure and sustainable energy future. It describes a world in 2040 where hundreds of millions of people still go without access to electricity and where CO2 emissions would lock in severe impacts from climate change. In this scenario, energy demand increases by 1% per year to 2040. Low-carbon sources, led by solar PV, supply more than half of this growth, and natural gas accounts for another third. Oil demand flattens out in the 2030s, and coal use edges lower. However, Laszlo explained that the momentum behind clean energy is insufficient to offset the effects of an expanding global economy and growing population. The rise in emissions slows but does not peak before 2040.

3) The Sustainable Development Scenario, indicating what needs to be done differently to fully achieve climate and other energy goals that policy makers around the world have set themselves. Achieving this scenario, in line with the Paris Agreement of limiting the rise in global temperatures to well below 2°C – requires rapid and widespread changes across all parts of the energy system. Sharp emission cuts are achieved thanks to multiple fuels and technologies providing efficient and cost-effective energy services for all. For this to happen, strong leadership from policy makers is needed, as governments hold the clearest responsibility to act and have the greatest scope to shape the future. Achieving the Sustainable Energy Scenario needs a grand coalition encompassing governments, investors, companies and everyone else who is committed to tackling climate change, Laszlo stresses.

Conclusions:

– Energy policies are adjusting to new pressures and imperatives, but the overall response is still far from adequate to meet the energy security and environmental threats the world now faces

– The oil & gas landscape is being profoundly reshaped by shale, ushering in a period of intense competition among suppliers & adding impetus to the rethink of company business models & strategies

– Solar, wind, storage & digital technologies are transforming the electricity sector, but an inclusive and deep transition also means tackling legacy issues from existing infrastructure

– Energy is vital for Africa’s development, and Africa’s energy future is increasingly influential for global trends as it undergoes the largest urbanisation the world has ever seen

– All have a part to play, but governments must take the lead in writing the next chapter in energy history and steering us onto a more secure and sustainable course

Laszlo’s intervention was followed by a short self-introduction of the 21 YPS participants. Marcus Lippold, energy expert and member of United Europe, then gave an introduction into the topic and an outlook over the 2-days seminar.

The second keynote was given by Prof. Dr.Dr.Dr.h.c. Franz Josef Radermacher, CEO of the Forschungsinstitut für anwendungsorientierte Wissensverarbeitung (FAW/n) in Ulm, Germany, via Skype-call.

Radermacher is a professor of Computer Science and an expert on global sustainable development, innovation and globalization, among others. He is on the executive board of the Research Institute for Applied Knowledge Processing, one of the co-founders of the Global Marshall Plan Initiative and supports the concept of a global Eco-Social Market Economy.

He presented his plan to recycle carbon fourfold in order to significantly reduce CO2 emissions to enable Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be reached by 2050 and the global energy and climate crisis to be resolved. Radermacher is convinced that a world sustaining prosperity for 10 billion people and protecting the climate system and environment at the same time is possible. He says that the challenges we are facing are not being overcome by despair resulting in the renunciation of valuable achievements of human history. Only with prosperity for everyone can we stabilize the size of the world’s population. Otherwise social upheavals, even to the point of (civil) war are likely.

Radermacher identifies three elements that need to be combined to achieve these goals: 1)A methanol economy, 2) soils as carbon storage and 3) carbon offsetting projects promoting SDG implementation. By recycling carbon four times on average in the context of a hydrogen/methanol economy CO2 emissions can be reduced from 34 billion tonnes to around 10 billion tonnes per year. This, combined with the use of soils as carbon storage and carbon sinks for the remaining 10 billion tonnes of CO2, will close the carbon cycle.

As a third point, Radermacher addresses the promotion of international development and related projects, which will also co-benefit all SGDs and create positive climate effects.

In the thirdkey note speech, Joel Couse highlighted several challenges for the oil and gas energy sector:

A first challenge is price volatility. The oil and gas industry is a cyclical commodity industry with volatile prices and it has long investment cycles. The advent of short cycle investment projects makes the business more financially fragile. Swing producers are now the shale oil and gas sector in the USA which aggravates the cyclicality. The economic model of the oil and gas majors however is unique. They deploy considerable financial resources and knowhow while absorbing risks both financial and technical across a broad portfolio of investments and activities. Strategies for robustness include countercyclical investment, regional diversification and value chain integration for oil, gas and power.

The second challenge is demand sustainability. Most forecasts show world energy demand growing on average by around 1% per year between now and 2040. Energy intensity or energy consumed per unit of GDP should decline steadily by more than 2% per year. That’s to be compared with the period from 2000 – 2018 when it declined by only 1.6% per year. Renewables and natural gas will account for about 40% each of the overall supply increase of energy and oil for about 12%, mainly for the transport and petrochemicals sector.

The evolution of the energy mix will be a move towards a low carbon electricity business. This is reflected in cost pressure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the necessity to improve efficiency through electrification. The long-term trend is towards renewables and batteries, but the evolution initially favours gas as a transition fuel. This rapidly boosts LNG requirements to feed new gas markets, producing LNG to connect best low cost resources in Russia, the US, Qatar or Australia with fast growing consumer markets in Asia requiring significant financial resources and technical knowhow, which are typical of the oil and gas companies.

The third challenge is climate change. Oil and gas companies take climate change seriously and support the goals of the Paris Agreement. The 13 members of the oil and gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) cover 30% of global oil and gas production. The companies actively aim to improve energy efficiency, to emit less CO2 to reduce gas flaring to near zero and to eliminate methane emissions both upstream and downstream. Some companies have numeric targets on energy efficiency gains for reducing the greenhouse gas intensity of their operations and have introduced governance mechanisms including remuneration to help meet those targets. As the future energy market will use more low carbon energy, some companies are developing low carbon energy businesses, including energy efficiency as well as investing in carbon sink businesses and natural sinks such as forests.

Afterwards, 5 participants presented five different seminar-relevant topics in short presentations:

1. Shradha Abt, Senior Specialist Energy and Climate Policy at BASF, demonstrated how BASF is adapting to climate change, CO2 reduction and industrial transformation.

2. Elif Dilmen, Senior Risk Advisor at Marsh in Turkey, explained how emissions reduction in aviation works.

3. Paula Amiama, Management Trainee in Digitalisation and Innovation at DB Schenker, explained the environmental service branch as a model for mitigating climate change.

4. Nejra Durakovic, Senior Energy Consultant at Alfa Energy Group Bosnia and Herzegovina, showed models for Climate Adaption and Mitigation in Europe, current plans and what has happened so far.

5. Samuel Zewdie, Client Executive in Trade Credit & Political Risk at Marsh Austria, explained how financial markets and their regulatory requirements can contribute to better pricing-in climate risk.

After lunch, Carine de Boissezon, Head of Sustainability at EDF Group, gave a speech on the role of finance and social aspects of climate change. EDF is a listed, 84% state owned French electricity company and the second largest electricity producer in the world.

In the first part of her speech, Carine focussed on the financial markets which only recently stepped up on the impact of climate change for the financial sector. This was triggered in 2015 by the Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, who stated that, if finance doesn’t think about the climate related risks on balance sheets, the financial system could face systemic risk. He raised awareness and a sense of urgency for the finance sector, achieving that climate has now been put firmly on the agenda. Most recently, the new EU Commission has taken strong leadership with the proposed Green Deal, and the European Investment Bank announced mid-November that it will stop funding fossil fuel projects by the end of 2021 including gas projects, with the aim to become Europe’s climate bank.

According to Carine, the EU Green Deal shows climate leadership. Yet, the EU alone will not be enough to win the fight against increasing levels of CO2. The challenge is how to get others engaged. As emerging countries, China and India generate significant amounts of CO2 in absolute terms, but argue that on a consumption per capita basis they are lagging developed countries. The trade war between the USA and China makes it even more complicated to create new momentum on climate action.

Carine also referred to the current climate conference in Madrid (COP25) and mentioned that many observers wonder whether this kind of format still works: a lot of discussions and negotiations with many people involved but not many actions.

If we want to survive by 2050, we need to stop the temperature increase by taking action and pushing the agenda in terms of commitments. A second important aspect is the social one. We have to ensure that the energy transition doesn’t create «stranded workers» Countries like Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic have not yet signed their commitments of carbon neutrality by 2050. It is a big issue for some countries how to manage the transition. Finance plays a key role in this regard. In the past, finance was not really looking at the social aspects. But now it is realized that the energy transition won’t happen without considering the social aspects.

Closing thermal or in the future nuclear assets has to be anticipated and properly managed. The job perspective is a crucial one as you need to ensure the right level of competence, which implies a significant investment in training for employees. EDF has signed ecological transition contracts with NGOs, unions, local regions in order to plan the transformation and to make sure that the social impact of the energy transition should be positive.

90% of the solar panels installed in Europe are produced in China or India. In Europe most solar companies have gone bust over the last 10 years. This is why we need to create European champions and need to defend our industry. According to Boissezon we need to push our voices to the European Union to make sure that this energy transition creates value in Europe.

At the end of her speech she drew attention to concertation and dialogue. Most of the projects failing do so not due to lack of financing, but because of the acceptance in the population. They are concerned about climate change and want renewable electricity – but they also refuse wind turbines in their vicinity (the NIMBY effect, Not in My Backyard). This could be the next challenge for solar if it was to be a massive deployment because it needs a lot of land.

Conclusion: We have to do something; we have to do it quick. Hard decisions and changes are approaching. We must try to achieve both: to stop global warming while preserving our industry, our jobs and thus our prosperity. But not only politics and industry are responsible. The population must be aware that global warming can only be defeated if they are ready for changes in their own sphere of life.

After a short Q & A, the participants started to work in 4 groups which were already created in the run-up of the seminar. The topics were:

Group 1:

The European 20/20/20 goals and the EU’s energy transition, where are we today?

Group 2:

A holistic view on global warming: the perpetrators (electricity, heat, mobility) and the balancing elements (clouds, oceans, vegetation)

Group 3:

How do companies respond to the challenges? How have they thus far been affected? Which companies have already taken action? Are there role models?

Group 4:

Recent energy transitions around the world: USA, China, and Japan

Saturday, 23rd November

The second day was devoted to working on the topics and creating presentations with the findings of the different groups.

After a creative, worked-filled day, the individual groups presented their findings and discussed them with the others:

GROUP 1: THE EUROPEAN 20/20/20 GOALS AND THE EU’S ENERGY TRANSITION

Marcin Markowski, Karl Wagner, Shradha Abt, Nejra Durakovic, Nico Gorgas

For more than a century people have been using and depleting energy resources carefree, as if they were endless. In 2020 the world could find itself in a deadlock. This is why the EU leaders have committed to a common goal in 2008, which is transforming Europe into a highly energy-efficient, low carbon economy. It is when the European Union has introduced the first package of the climate and energy measures for 2020:

– 20% reduction in GHG emissions, compared to 1990 levels,

– 20% of the energy, based on consumption, coming from renewables, compared to 1990 levels and

– 20% increase in energy efficiency, compared to 1990 levels.

Status as at today

• Well on track → GHG target, -23% (in 2018) with GDP increase by 61%

• Not on track → RES 17.5% (2018) – with e.g. NL worst performing

• Not on track →Efficiency 17% (in 2018) – target could be met depending on energy consumption habits in coming period

Taking a sectoral approach

Meeting the targets is based on abatement potential, so we looked at the five highest emitting sectors and how these sectors helped meet the EU targets: contribution towards the difference targets, what were the main issues, and what were the drivers for the I) power sector, II) industry, III) transport, IV) residential and V) agriculture.

I. Power Sector:

The decrease in emissions was mainly driven by the power sector. Thanks to progressing coal phase-out and increasing integration of renewable energy sources (32.3% of EU electricity production in 2018) greenhouse gases emissions were reduced by 26% between 2005 and 2016. Transition from hard coal and lignite is moving forward Community-wide but is hindered in some regions due to substantial political and socio-economic reasons. In Poland, for example, more than 96,000 people were employed in mining (coal and lignite) in 2015, the country is 80% dependent on coal and is not yet in a position to immediately implement the required “green deal” measures.

II. Main Drivers in lowering the GHG for the industry sector would be:

1. ETS (including free allowances):

Balancing the right carbon taxation and the right emission thresholds by using other specified parameters depending on the industry and the produced amount of GHG’s, could lead to the need of more drastic industry measurements in order to reach free allowance standards.

2. Improved efficiency:

Energy efficiency not only cuts GHG’s but also reduces production costs

3. Changes in the supply chain:

Interconnection between all stakeholders for a holistic approach throughout the supply chain. Alternative products and supply routes can play a major role in the final ecological footprint.

III. Transport sector

After a decrease in emissions between 2007 and 2013, emissions from transport have increased in each of the last five years and are now only 3% lower than in 2005. Towards 2030, member states project a small reduction (7% compared to 2005) with existing measures. However, with implementation of planned policies and measures, transport emissions are projected to be reduced by 18% by 2030, compared to 2005.

Main drivers and long-term strategy options which could contribute to reducing CO2 emissions in the transport sector are:

– CO2 emissions standards for new cars, vans and heavy-duty vehicles

– Electrification: faster electrification for all transport models

– Extending railway structure: shift transport from road to rail

– Hydrogen: H2 development for HDV’s and some for LDV’s

– Power-to-X: E-fuels deployment for all models (this scenario assumes an intensive use of

e-fuels, i.e. synthetic fuels made with renewable power, so a large amount of electricity

would have to be produced, e.g. in the aviation sector)

– Energy efficiency: increased modal shift

– Circular economy: mobility as a service

IV. Residential Sector

As for the residential sector, in the time span 2005 – 2018, it has recorded 50% of CO2 emission reduction. Main issues here are the lack of housing renovation, which inevitably draws the financing issues; the heating and cooling systems in buildings, which are not as efficient and, in many cases, are obsolete. And the fragmented construction sector – where for any residential work, we need to employ many different parties to get the work done. Main regulatory drivers for the residential sector would be: EPBD – Energy Performance of Buildings directive, Energy Efficiency Directive – EED and other standards.

V. Agriculture

Over the period: 2008 – 2015, there has been only 1.07% reduction in GHG.

The imposition of measures to the farmers such as taxes can reduce significantly their income thus causing unrest. For that reason, measures have to have a more rewarding rather a punitive nature.

As this sector has great value to all citizens it is hard to apply restrictive regulations. Additionally, with urbanism being a major issue, the preservation of the population in rural areas is an important factor.

Main drivers which could help in lowering the CO2 emissions in the agricultural sector are:

1. Careful Planning and Land Crisis management

2. Energy and Fuel efficiency increase

3. Improved irrigation and fertilizer application

4. Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) to support in a rigorous way the innovative agricultural and rural practices.

5. LULUCF: Consultation on the green paper and the commitment to the reduction of GHG’s with the member states proving their supportive measures through the Land Use, Land USE Change and Forestry (LULUCF).

GROUP 2: A HOLISTIC VIEW ON GLOBAL WARMING

Paula Amiama, Solomon Elliott, Tim Cholibois, Cécile Boucher, Karl Toomet, Mihkel Kaevats

Rapid and irreversible climate change poses one of the biggest threats to future generations. In order to raise public awareness holistically, the team developed a card game for students that teaches the basic elements of climate science in a playful and interactive manner. Carbon Clash divides our impact on the planet into four categories: energy production, mobility, food and material use. The cards within every category are ranked in a hierarchical order from activities that have the least impact to those that are most impactful in terms of carbon emissions. Every card – e.g “Burning coal” in energy production or “Taking a train journey” in mobility – includes a short yet comprehensive explanation on the card itself and it is connected to an online wiki / a physical manual for further detail. The result is an engaging learning experience for students to increase climate science literacy in a truly fun way. The team is currently developing a first prototype of Carbon Clash in order to test it with different target audiences across Europe. This is interesting not least because more and more schools are addressing the issue of climate change and Italy even wants to make it a legal school subject.

GROUP 3: HOW DO COMPANIES RESPOND TO THE CHALLENGES?

Isabel Schulze-Berndt, Hanna Ritari, Dimitrios Vouropoulos, Elif Dilmen,

Anna Chashchyna, Kalina Trendafilova

Companies are exposed to a number of climate change -related challenges in the form of physical, financial and transition risks. The risks are diverse and include, for example, business disruptions due to extreme weather events that affect production and the supply chain, price volatility of raw materials, increased costs due to changing legislation or reputational risks due to the inability to respond to changing business requirements. Climate change is an ever more acute challenge for companies. For example, the economic impact of natural disasters has exploded from USD 200 bn in the period of 1970-1979 to USD 1400 bn in the period of 2010-2017 (Marsh, 2018).

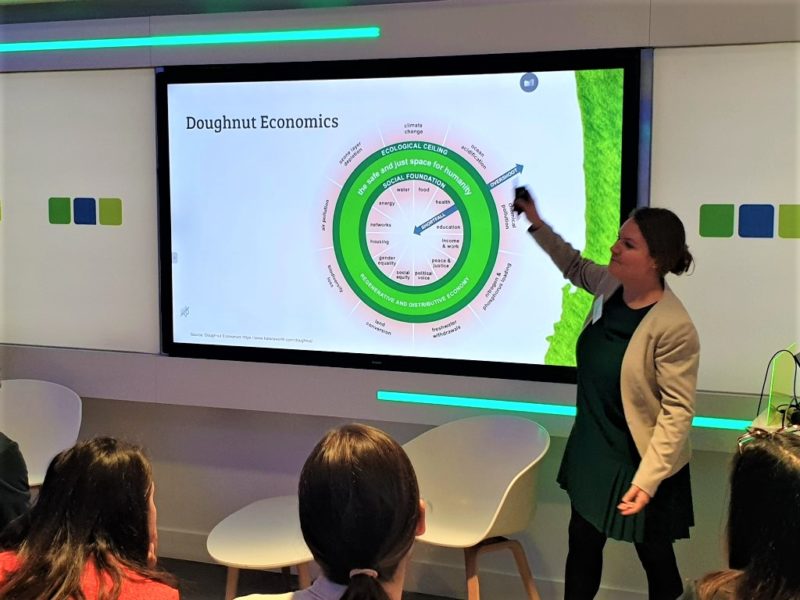

Leading companies are, however, turning the fight against climate change to their benefit, and many companies see climate action as a driver for growth, competitive advantage and innovation. The circular economy is a good example that combines climate change mitigation and business opportunity, enabling new business models and developing new markets, domestically and outside the EU. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a shift towards a circular economy could reduce net resource spending in the EU by EUR 600 bn annually by 2030, bringing total benefits amounting to EUR 1.8 trillion per year once multiplier effects are accounted for.

The circular economy can have a particularly strong impact in the food industry in the EU where 20% of food produced annually is lost or wasted. There are already a number of companies taking advantage of this lost potential through dynamic pricing of perishable food items, such as the Dutch company Wasteless, for example, or by creating marketplaces for unused food in restaurants, such as the Danish company Too Good to Go, which now operates throughout Europe.

In addition to seizing these completely new business opportunities, many companies are also committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions in their existing business. Half of Fortune 500 companies already have emissions reduction or clean energy targets, and nearly 700 companies have committed to setting a science-based emissions reduction target in line with the Paris Agreement. Many companies are also striving to reduce their water consumption and announcing additional investments in the development of low-carbon technologies. However, based on a 2016 survey by Bain & Company, only 2% of companies’ sustainability programs achieve or exceed expectations and over 80% result in mediocre or unclear performance. This paints a somewhat worrisome picture of companies’ sustainability initiatives. A possible explanation of this is that today, sustainability targets and actions seem to be hard to measure. An indication of this was provided by a study conducted in the MIT Sloan School of Management where the scores of five major ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) rating providers were compared. The ratings differed dramatically for a single company, the range of correlations being from 0,42 to 0,73 compared to that of 0,99 for Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s credit ratings (Berg et al., 2019). It seems that the saying “you can’t manage what you can’t measure” seems to hold true particularly in the case of sustainability initiatives.

One potential solution that could incentivize companies to take even bolder action to fight climate change can be found in policy measures. Paul Polman, the CEO of Unilever, accurately pointed out that “business needs three things from the political community: clarity, confidence, and perhaps most of all, courage” (UN Global Compact, We Mean Business, WRI, 2018). Thus, clear and ambitious regulation and long-term signals for the markets can push both investors and companies to accelerate their climate action and ultimately, help bridge the gap between company ambitions and actions.

GROUP 4: RECENT ENERGY TRANSITIONS AROUND THE WORLD: USA, CHINA, AND JAPAN

Dinand Drankier, Julien Hoez, Vera Mitteregger, Nevena Milutinovic, Samuel Zewdie

While we know about what’s happening in Europe, the EU is not the primary contributor when it comes to Climate Change. Its actions to reduce its emissions have a relative level of success. However, we can learn from the situation regarding China and the US, two of the largest global polluters, and from Japan, a major industrialised state.

USA

After US-President Obama had ratified the Paris Agreement in 2015, his successor Donald Trump announced to withdraw from it.

Since the GHG emissions in 2017 were only reduced by -13 % compared to 2005, the US is not on track to meet its NDC set by the Obama administration which requires a reduction of 26 – 28% by 2025.

An important particularity of the United States is the considerable political authority that the individual states have in the field of energy. In the absence of ambitious federal policies in the field of renewable energy or greenhouse gas emissions reduction, the states have come up with their own policies and ambitions in terms of decarbonization.

At this moment, 29 states, the federal district of Washington, D.C. and three territories have adopted obligatory standards, so-called Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPSs), that oblige electricity supply companies to assure that a certain percentage of their supplied electricity is from renewable or clean origin. In addition to binding standards, another eight states and one territory have set a renewable energy goal. In terms of ambition, 10 states, the District of Columbia and the territory of Puerto Rico have pledged to fully decarbonize their electricity supply in or before 2050.

To promote renewable energy production and the deployment of zero-emissions vehicles (ZEVs), multiple states have in place tax credit or reduction measures. Nine north-eastern states have moreover joined forces in a regional cap-and-trade system to reduce the emissions emanating from the power sector. To also reduce emissions from manufacturing, the state of California has put in place a cap-and-trade system that also covers this sector.

Although many of these measures are at their current level of ambition or their current level of coverage insufficient to put the US on track for a well below 2°C world, the steady progression of ambitions and coverage of state level policies, as well as the steady growth of the renewable energy industry in the United States on the basis of its own value proposition and competitiveness provides some reason for optimism.

China

China is the largest contributor to global energy consumption growth for the 18th consecutive year. It accounted for 24% of global energy consumption and 34% of global energy consumption growth in 2018. The energy consumption increased at 4.3% in 2018, from 3.3% in 2017 and a 10-year average of 3.9% and is still expected to grow.

The energy system is characterized by low energy efficiency, heavily dominated by the industry sector with high energy consumption. Today the industry sector consumes almost 60% of the total energy consumption, a much higher share than in other countries. Imports are accounted for 70 % of oil consumption and 45% of gas consumption.

China is under pressure of carbon reduction: CO2 emission and energy intensity are decreased. Electricity generated from thermal power plants grew 6.7% and secondary industry’s energy consumption grew 7.6% → economic output outpacing growth in carbon emissions and energy use.

China has to scale up other energy sources as well as restricting coal use in key regions. Although raw coal production increased by 4.5%, its share in total primary energy consumption declined below 60% for the first time in 2018.

Summary

1.Change of Chinese economic structure

Transforming the industry sector from heavy industry with high energy consumption to lighter industry and service with less dependence on energy as input

2.Digitalization

Development of Internet of things, electrification of the transport sector, and use of big data as an integrated part of the industry and service sectors. This development requires electricity, not fossil fuels, as input

3.Improvement of new technologies for power supply

Wind and Power supply have developed to a technical stable and economically viable alternative power

Japan

● Japan’s energy landscape has been shaped by two huge events in the country’s history

○ the oil shocks of the 1970s (realizing their dependency on other countries)

○ Fukushima earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011

● Before Fukushima – Japan was the world’s third-largest generator of nuclear electricity behind the U.S. and France

● After Fukushima (2013) – turned to gas and oil

○ Gas 42%

○ Oil 15%

○ Coal 31%

PLAN: double the number of renewables in its power supply to 20% by 2023.

CONCLUSIONS:

Taking into consideration these observations, the question arises which lessons Europe can draw from the developments in the United States, China and Japan. A first point to take from the above comparison is that each country has a unique energy system due to differences in for example natural endowment, economic situation and political context. Approaches to the energy transition which work in one country can therefore not be transferred easily to other states. The Chinese top-down approach to designing and implementing the energy transition would hardly be feasible for Europe, where public participation and consultation, stakeholder management and consensual politics are seen as key prerequisites for an effective energy transition.

A second point that has been highlighted in this comparison is that Europe is not the only place in the world where an energy transition is taking place. Even though the energy transitions in the United States, China and Japan take a different approach in terms of ambition and focus areas, areas of overlap and common interest can be identified, such as the hydrogen economy, offshore wind, and optimising (bio-)resource utilisation. Climate diplomacy, best practice sharing, policy linkages with innovation and industrial policy, and international cooperation can be a fruitful way for Europe to foster more active climate policies and to support the adoption of low-carbon technologies abroad.

Focussing on particular lessons that can be taken from the three countries investigated, two lessons stand out. First of all, it’s important to observe that the energy transition is also about shifts in industrial activity and different modes of value creation. While fossil-based industries will lose their value over time, innovative carbon neutral technologies will become the drivers of the future economy. Combining energy policy with industrial policy is therefore of great importance. Companies from China and Japan have a large market share in the production of renewable energy hardware, such as photovoltaics, and are making big steps in renewable energy technologies like hydrogen. In order to be able to be competitive in a global market, Europe should focus more on creating European champions in the field of renewable energy production and clean industrial and chemical processes. The EU Commission should therefore in its Green Deal look at ways to promote collaborative and innovative company ecosystems and global European players. Also assessing potential barriers, stemming for example from consumer-centric competition law requirements, and ways to balance these concerns with the need for a consolidated European answer to foreign competition might be appropriate points to include in the European Green Deal.

Secondly, as has become clear from the experience in the United States, a central government is not the only player that can fuel an energy transition: sub-national governments and companies also play a large role in this.

Also in the European context, the energy transition is a multi-level phenomenon with the EU, national governments, regional governments and local governments all playing their role.

Here, a clear relation exists to for example the “Europe of Regions” seminar organised by United Europe in Budapest in October 2018. Focussing on integrated regional approaches to the energy transition and the role of regions can provide important lessons and templates. Regionally deciding on how to give form to the energy transition and how to integrate the energy transition in the regional landscape, taking into consideration regional particularities, can be a good way to facilitate the transition.

It thus has to be extremely well coordinated across all relevant players, including society at large. Furthermore, at this stage of the major transition towards complete decarbonisation by 2050, regulators and governments should stay very open-minded regarding technologies and applications that will make a difference in the future, including those that might not exist yet which R+D is looking at. As the IEA has highlighted in their latest WEO, all technologies and most fuels/ energy forms will be needed still in the future, so it would be wrong to pick ‘winners’ at this stage already, with the risk of getting locked-in to early generation technologies which are only partially efficient. This applies to certain EU member states already today.

Combining all these lessons, it can be summarized that the European answer to the energy transition should be based on what Europe is best at: being competitive and diverse.

We thank ENEDIS for the generous support!