European Union

Under combined pressure from migrants and terrorists, the Schengen area – the European Union’s control-free travel zone – could become a thing of the past. Many member states have enacted temporary restrictions at their borders; some have even built razor-wire barriers to stave off perceived threats to their stability and security. The Schengen system, once designed to protect Europeans, is widely questioned. In May 2016, Brussels authorized an extension of such extraordinary measures for another six months. Salvaging the system is still possible, but not certain.

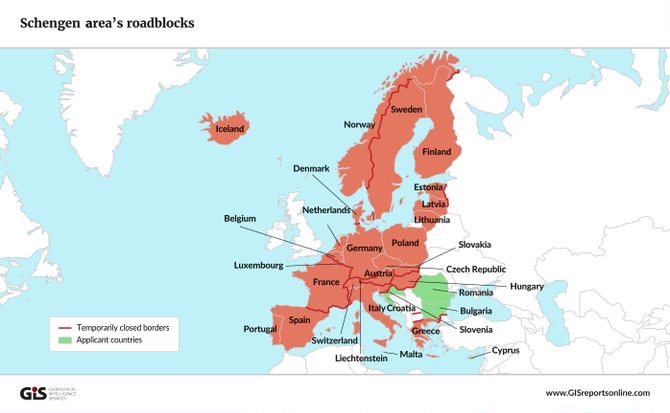

The Schengen area is the European control-free travel zone designed in 1985 with five EU member states; today it bonds 26 European nations, with Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Ireland, Romania and the United Kingdom the only members of the bloc remaining outside the system. The area embodies the values of free movement of people, goods, services and capital within Europe and stands as possibly the biggest achievement of the 60 years of European integration – a crucial component of the single market. Its economic, political and psychological role cannot be overestimated. But Schengen is now undermined by ill-controlled migration from the Middle East and Africa and fears of more terrorist attacks. Clouds hang over its future.

The zone’s benefits

Hassle-free border crossing helps generate revenue from tourism and makes life a lot easier for commuters, businesspeople and of course for truckers transporting goods across the zone. The creation and expansion of the system have increased the extent of Europe’s market, spurring commerce and encouraging an economically beneficial division of labor. Also, the growing interdependence of the continent’s parts has made Europeans less nationalistic (except in times of crisis) and aware of their common heritage. Schengen spawned close ties between Europe’s civil societies, helping to build a sense of European “togetherness.” As Montesquieu could have argued, the economic and human integration enabled by Schengen’s “doux commerce” has strengthened European peace.

Schengen spawned close ties between Europe’s civil societies

For a year or so, however, this momentous accomplishment has been under strain. One culprit has been the migrant crisis. The ongoing conflict in Syria and migration waves from the Middle East and Africa, intensified by human trafficking (an estimated 5 to 6 billion euro business in 2015), together pumped a record number of asylum seekers into the EU last year. While Germany welcomed them at first, many countries along the route to it quickly began to resent the caravan through their territories and blocked it. Flooded with more than a million refugees, Germany eventually had no choice but to impose temporary border controls as well. Despite the loss of life and immense suffering of migrants, their sheer numbers scared many Europeans. With no clear solution in sight for neither the Europeans nor for the refugees, despair and frustration set in across the continent.

Weather change

Small wonder that such tensions translate into anti-immigration measures now, traditionally advocated by right-wing parties such as the National Front in France, Jobbik in Hungary, or Alternative for Germany. Ugly incidents blamed on migrants, such as a string of sexual assaults on New Year’s Eve in Cologne, further inflame emotions. Policymakers have had to pay heed to their constituencies’ mood. As the extolled “European solidarity” failed to materialize, with most countries trying simply to push refugees onto their neighbors, a sentiment of unfairness and conflict arose among EU members. Restricting the influx of migrants became imperative for most policymakers, whatever the risk for Schengen.

The terror attacks in Paris in November 2015 and in Brussels in March 2016 provided further rationalization for suspending Schengen. Open borders make it easier for terrorists to move around and a Paris terrorist actually entered the EU as a Syrian refugee. Another, less recent, argument for the curbs is the observed ability of organized burglar groups to quickly escape national police hunts. All these factors have colluded in casting doubt over governments’ ability to ensure basic security under Schengen rules.

Schengen-less Europe

Losing Schengen would probably destroy the feeling of “Europeanness” and mutual trust that has evolved over a generation. A rise in nationalism could follow. Of course, there also would be economic costs, ranging from falling tourism revenue and fewer business deals – which means less foreign direct investment (FDI) – to import- and export-crippling queues of trucks at congested border crossings. Europeans would belatedly appreciate the worth of the Schengen system they today take for granted. Add to that the cost of recreating borders with fences, tolls etc., plus the expenditure of hiring customs personnel and of expanded administration.

Various estimates for these costs have been offered. In February 2016, the French government think tank France Strategie put the cost of dropping Schengen at 110 billion euros over a decade (10 billion euros for France alone). The estimate did not include the cost of recreating border control systems or the impact on FDI, or reduced labor mobility. Ending Schengen “would be equivalent to a 3 percent tax on trade,” leading “to a structural decline in trade of 10 to 20 percent,” the report’s authors concluded. The European Parliament’s more exhaustive recent study finds a loss of 100 to 230 billion euros over 10 years in the case of a permanent retreat from Schengen. The Bertelsmann Foundation in Germany is even more pessimistic, with its estimate of total economic loss at between 500 billion and 1.4 trillion euros over 2016-2025 – with 77 billion to 235 billion euros for Germany alone.

The European Parliament’s study finds a loss of 100 to 230 billion euros over 10 years in the case of a permanent retreat from Schengen

A less wealthy Europe would also mean economic consequences for its partners, especially China and the United States. Which, in turn, would bring more bad news for Europe, not unlike during the spiraling into depression during the 1930s. A retreat from Schengen would also likely spell an end to the common currency, as the European single market would be broken. Yet, the possible ways to salvage Schengen are not without problems of their own.

Greeks apart

Until April 2016, Greece was the main point of entry for migrants from the Middle East and Africa, accounting for more than 80 percent of the traffic. The country had a tendency to be lax on enforcing Schengen rules and in many cases simply let newcomers transfer further north. This was met with sharp criticism from the affected countries; there were even calls for expelling Greece from Schengen. However, just like in the case of Greece’s public finances, Brussels has been aware for years of the country’s substandard practices. It was a bit hypocritical for the EU to suddenly become enraged over the Greeks’ poor guarding of the Schengen border. Furthermore, the Greeks have been caught in the vise of severe debt and political crises since 2010 and thus have had few resources to dedicate to immigrant assistance. In this context, Athens’ claims of having spent 2 billion euros on that and its calls for EU solidarity were easy to make.

Tensions within Greece, and between Greece and the EU, piled up as the blame game continued. Looking at the big geopolitical chessboard, Brussels was probably aware that Vladimir Putin’s Russia was watching for an opening to further disrupt the EU. Expelling Greece would turn that country into a massive migrant camp and further undermine regional stability. In March 2016, material support was promised to Greece, with a caveat that rules must be applied – especially identification and registration of all entrants. Frontex, the EU agency tasked with border control coordination and stopping illegal immigration, sent additional personnel to Greek waters in April.

It was clear that the next necessary step was to block departures from Turkey.

Turkish dawn?

Turkey sits smack on the natural route for Syrian migrants headed for Greece. With more than 2.7 million Syrians on its territory already, Turkey must be party to any conceivable solution to the crisis. Brussels struck a deal with Ankara in March. Turkey agreed to keep migrants and prevent them from crossing into Greece via the Turkish-Aegean route thus reducing the number of tragic deaths at sea and, politically, helping to save Schengen. The deal included a provision for readmitting in Turkey those refugees who had not applied for asylum or whose application had been turned down by the Greek authorities. Also, the EU would accept one Syrian refugee from Turkey for each refugee readmitted in Turkey from Greece.

In return, Ankara was to receive 3 billion euros in aid and its accession talks with the EU would resume. In the following May the head of Frontex announced that “Turkey has delivered”: the number of migrants crossing the Aegean Sea in April fell by 90 percent, to some 2,700 persons. At the same time, 8,370 refugees reached Italy.

Turkey agreed to keep migrants and prevent them from crossing into Greece via the Turkish-Aegean route thus helping to save Schengen

But will the deal hold? It was sweetened by a promise of visa-free travel for Turkish citizens. This, though, is conditioned on Turkey’s improving its record on human rights – at a time when the government of Recep Tayyip Erdogan is criticized for Turkey’s antiterror laws and the jailing of journalists and critics. Many in Europe see elements of blackmail in the deal. In fact, Turkey missed a June deadline for meeting EU’s conditions set for allowing its citizens visa-free travel in the Schengen zone. Ankara’s unwillingness to soften its antiterror measures proved to be a particularly big roadblock.

A second issue is that the man who efficiently dealt with the migrant trafficking out of Turkey was former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, fired from his job in early May by Mr. Erdogan. Today, the deal seems fragile.

It is even more so because it foresees freedom for 80 million Turks, most of them Muslim, to travel to Europe. Many European citizens and politicians with not exactly pro-Muslim positions will find that hard to accept under current circumstances. In effect, the pact meant to protect Schengen by itself poses a threat to Schengen.

Aware of the problems, the EU is probably buying time now, nitpicking during the talks on the pact’s details, with apparent hope that the inflow of migrants somehow won’t resume. It may prove shortsighted, though, to play such games with a “gatekeeper” that has as much leverage as Turkey does.

Foreign partnerships

It is not only Turkey that poses a tricky problem for EU leaders these days. In early June, the European Commission announced a “New Migration Partnership Framework,” a program offering some 8 billion euros in targeted aid to countries where migrations originate – such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, or African countries such as Mali and Nigeria – or are on the transit routes, such as Libya. The idea behind the program is to invest at least some EU taxpayers money in attempts to stem migrations by spurring economic growth in the poorest areas, and on assisting transit countries with technical aspects of illegal outflows prevention, such as improving their capacities in border management.

The approach appears rational, the ideas look good on paper. At closer scrutiny, though, they entail at least three political risks. Some will say that the commission has found a way to expand its aid industry. Any increase in “forced solidarity” with taxpayers’ money and bureaucracy expansion stands to anger Euroskeptics. The risk is also that this expanded bureaucracy will not be efficient enough to actually make headway in solving the problems. Worse still, the measure may defeat its stated objective. Experience from many decades of offering foreign aid to the developing world shows clearly that giving money to corrupt regimes more often than not hurts development, giving hapless people new incentives to migrate. “Unscrupulous smugglers” often fingered by Brussels officials are an issue; unscrupulous leaders can pose even a bigger challenge to the West’s aid schemes.

Back to basics

Whether EU leaders will be able to salvage Schengen now largely depends on their ability to implement pragmatic policies – as they managed to do, to an extent, in March and April of this year. Confusion and conflict arise largely from different views on what European “solidarity” is supposed to mean; all too often, the term has been used to excuse irresponsible behavior or as a pretext to sponsor the growth of the so-called “salutary” bureaucracy, as happened during the last financial crisis.

Will the EU get back to basics? If Schengen rules are not forcefully upheld, if responsibilities can be questioned and the notion of “solidarity” is marred with duplicity, then it is hard to see a positive scenario. For example, out of the 160,000 migrants who were supposed to be relocated from Greece and Italy, only 2,000 or so have been admitted by other countries. This Schengen crisis is a test of democratic maturity for the EU and its members.

In the present context, secure borders are the EU’s first commons. If the EU is not able to set up a truly effective system of guarding its land and sea borders, as it promised in December to do, if information sharing and cooperation do not materialize, if there is no interoperability of the information systems as discussed in April, the battle to defend Schengen and “fortress Europe” will simply be lost.

At the same time, there lurks a deeper question about this fortress. It is true that huge waves of migrants are not easy to handle. But the evident inability of the wealthy Europe to absorb migrants is so alarming because it is structural. Humans are not a burden; they constitute an opportunity to create value. That Europeans insist on perceiving opportunities as threats tells a disturbing tale of today’s Europe. This civilization can no longer open up because of its overregulated labor and housing markets, and because of its overly costly, exclusionary social welfare systems. In such a context, migrations create only conflict, not value.

Despite their common free market zone, European societies are increasingly sclerotic and inflexible.

This report has been written by Dr. Emmanuel Martin and made available to our members through the courtesy of © Geopolitical Information Service AG, Vaduz:

www.geopolitical-info.com