The Eastern Partnership Summit on May 21 and 22 demonstrated how uneasy the European Union has become over its efforts to influence countries in its eastern neighbourhood. Officials and leaders of the EU’s 28-member states were cautious in vowing to strengthen ties with six former-Soviet republics knowing full well that any new pledges would risk enraging Moscow. This means Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia, whose greatest hopes were an association with the EU – now stand to see those aspirations dashed. This could spell the end for the EU’s eastern expansion plans.

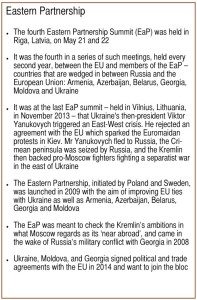

THE EUROPEAN UNION’S aspirations for eastern expansion are over. This was highlighted by the outcome of the Eastern Partnership Summit in Latvia’s capital, Riga, on May 21 and 22, 2015, where EU members hedged around the discussion of closer ties between Europe and its eastern neighbours dashing the hopes of those seeking a hard promise of EU membership. The talks between EU officials and leaders and six ex- Soviet states took place under a dark cloud of concerns about Russian aggression against Ukraine, and of fears that further ‘non-conventional’ operations might be carried out against other members of the EaP. If any of the invited governments had nurtured hopes they would be offered assurance against such eventualities, they left disappointed. The summit demonstrated how uneasy many European Union members are about confronting Moscow. Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova were left feeling sidelined.

Confrontation

The EU has been badly burnt in recent years, both by the outcome of the Arab Spring and by the confrontation with Russia over Ukraine. It is no longer in any mood to project power of any sort into its troubled neighbourhood. Important countries such as Italy and Spain view the EaP as a cause behind the rapid deterioration in relations with Russia.

The Riga Summit may be viewed as a true game changer – the time when Brussels decided to relinquish its previous ambition to use soft power to promote democracy and human rights, for an emphasis on security and reduced confrontation.

It is quite a transformation and few will be willing to admit openly this is the case. But when the summit microphones were turned off, there would have been a general recognition that the game of EU eastern enlargement was over. The transformation becomes less striking if we consider the background of political pressures, wishful thinking and policy inconsistency which have marked the attitude of many member states to further enlargement, arguably even before the decisions to admit Bulgaria and Romania, in 2007, not to mention Croatia, in 2013.

Special partnerships

The very idea of forming special ‘partnerships’ with non- member states arose out of the EU’s earlier and broader European Neighborhood Policy (ENP). It was formulated in 2004 to provide consolation for those neighbouring countries which were not earmarked for membership in the near future.

European Commission President Romano Prodi spoke, at the time, of a ‘Wider Europe’ consisting of a ‘ring of friends’ from Murmansk to Marrakesh. It was viewed at the time as a flagship of EU foreign policy. But it was a vision which would soon turn sour, and for good reasons. The agreements on partnership which would be concluded with countries in the east as well as in the south were something of a hollow deal. They promised practically everything which can stabilise a country but stopped short of coveted full membership. Brussels has been conspicuously wary of referring to the fact that the Treaty on European Union (originally signed in Maastricht in 1992) clearly states that any European state which respects EU values ‘may apply to become a member of the Union’. The substitute has been a vague notion of a ‘membership perspective’ which, over time, would be diluted to the point of irrelevance.

Russian assertiveness

The Eastern Partnership was formed in Prague, in May 2009. It was created in response to increasing Russian assertiveness against countries in what the Kremlin defined as its ‘near abroad’, an assertiveness that came to the fore with the war in Georgia in August 2008.

The agenda was driven by Poland and Sweden, with grudging support from other member states. The economic rationale was weak. Ukraine accounted for only two per cent of EU trade. Georgia and Moldova were not even on the radar. The main argument was soft power to promote common values.

At the Warsaw Summit in 2011, participants affirmed their commitment to ‘a community of values and principles of liberty, democracy, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and the rule of law’. The communique included the key phrase of acknowledging ‘the European aspirations and the European choice of some partners and their commitment to build deep and sustainable democracy’.

The geopolitics surrounding the partnership had changed substantially by the time of the 2013 Summit held in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius.

Human rights

Belarus was firmly in the Russian fold. Armenia had buckled under Russian pressure and opted to join a Russian-led Customs Union. Azerbaijan had tired of being browbeaten over its human rights, but remained convinced that Europe would want its energy.

Most importantly, Ukraine’s President Viktor Yanukovych had bowed to Russian pressure not to sign, thus triggering an insurrection at home which would lead to his downfall and eventually to war with pro-Russian separatists. The only countries that signed association agreements in Vilnius were Georgia and Moldova. Despite this fact, the Summit communique still included the ‘acknowledgement of the European aspirations and the European choice of some partners and their commitment to build deep and sustainable democracy’. And it stated, crucially, that, ‘the participants reaffirm the particular role for the Partnership to support those who seek an ever closer relationship with the EU’. Brussels remained strangely defiant in its ambitions. By June 2014 the new government in Kiev had signed the controversial association agreement, only to discover that Russian pressure caused the implementation of the free trade section to be delayed until the end of 2015.

Ambition and goals

Coming out of Riga, not even the language is there anymore. This year’s 2015 communique reaffirms ‘the sovereign right of each partner freely to choose the level of ambition and the goals to which it aspires in its relations with the European Union’, adding, ‘It is for the EU and its sovereign partners to decide on how they want to proceed in their relations.’ And there is nothing about any particular role for the Partnership to support those who ‘seek an ever closer relationship with the EU’. This is not quite the same as before.

An early indication that the EaP was being reduced to an empty shell was provided in September 2014, when Johannes Hahn, the Commissioner-designate for European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, stressed the need to revise the ENP as a whole.

Alarm was raised in January 2015, when the EU foreign affairs chief Federica Mogherini circulated a draft paper asking foreign ministers to consider ‘possible elements for selective and gradual re-engagement’ with Moscow.

Energy security

On March 4, Ms Mogherini joined with Commissioner Hahn in presenting a new document to examine the soundness of current policy. The main gist was that the EU must ‘stress its own interest when it discusses with its partners’, and that there must be a ‘new emphasis on energy security and organised crime’, as well as on terrorism and the management of migration flows.

Looking towards the future, the only real winner seems to be Belarus, whose President Alexander Lukashenko was, until recently, labelled the last dictator in Europe.

He has emerged centre stage, following the two sets of ceasefire negations for Ukraine which have been held in Minsk, He now signals he wants closer relations with the EU. And in preparation for the Riga Summit his ambassador, Vladimir Makei, emphasised the need for a non-confrontational, pragmatic approach.

Most importantly, at a meeting in Minsk on May 11, President Lukashenko met with Chinese President Xi Jinping to discuss the role of Belarus in the creation of a modern version of the ancient Silk Road trade route, allowing China overland access to European markets. Beijing pledged to extend US$3.5bn in credit and investments to banks and companies in Belarus.

Frozen conflict

Concerning Armenia and Azerbaijan, the EU remains hopeful that mediation will succeed in resolving the frozen conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh which has been simmering since the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. But the fact that Baku has disassociated itself from the Riga declaration does not make that a likely outcome. The two countries which did sign the agreement with the EU in Vilnius – Georgia and Moldova – face the risk of being hung out to dry. Both are marked by frozen conflicts that offer little prospect of being resolved. Georgia has been forced to witness Russian recognition of the breakaway provinces Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states, with which Moscow has finalised EU- style association and free trade agreements. The EU has no ambition to intervene. Moldova has long been forced to live with a de facto Russian protectorate in Transnistria. Like Georgia, it has little reason to hope for help from the EU in resolving the issue. Moldova is showing signs of becoming wary. Romania has expressed concern that a weak minority government formed in January 2015 may be forced to draw support from the anti- European Communist party, thus jeopardising the country’s relations to the EU.

Ukraine and the EU finally signed an agreement at the Riga Summit for an additional 1.8 billion euro loan to Ukraine. It is the third macrofinancial assistance programme the EU has given to Ukraine – the largest macrofinancial assistance programme ever awarded to a non-EU country. This came with qualified promises that Kiev, along with Georgia, was on a path to securing visa-free travel to Europe.

It may be viewed as small change, and Ukraine could be satisfied that Russia no longer objects to it implementing the free trade agreement with the EU. But this falls far short of hopes expressed by Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Pavlo Klimkin to the German daily newspaper Die Welt, that his government wanted ‘concrete assurances’ and a roadmap for EU membership.

Kiev did not even get the much hoped-for visa-free travel. This may come next year. As European Council President, Donald Tusk, noted in his final remarks, ‘It is, of course, also up to Georgia and Ukraine to set the pace when it comes to fulfilling the necessary steps.’

Empty promise

Mr Tusk said earlier that former Soviet republics such as Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine had the right to aspire to EU membership but he would not deliver an ‘empty promise’ about the prospects of such integration.

The partnership programme was never a guarantee of EU membership, even in the future, said Mr Tusk, but that the former Soviet republics had ‘their right to have a dream, also the European dream.’

As things now stand, those who have placed the greatest hopes in an association with the EU stand to be big losers. Ukraine is being left to drift towards sovereign default and status as a failed state. Georgia is left to deal with increasing Russian pressure, and Moldova may succumb to internal pressures to reorient away from the EU. Brussels meanwhile is deluded if it thinks it can ignore the fallout from expectations it has created – and simply walk away. The eventual bill for picking up the pieces in Ukraine will far exceed that of Greece. Accusations of betrayal will split member states into camps which will further aggravate the crisis in relations to Russia. No one has captured the essence of the crisis in the neighbourhood policy better than German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Speaking in front of the Berlin parliament on May 21, before leaving for the Summit in Riga, she said, ‘We must not create false expectations.’ It would have been better for all concerned if that warning had been issued in 2009.

This report has been written by Professor Stefan Hedlund and made available to our members through the courtesy of © Geopolitical Information Service AG, Vaduz:

www.geopolitical-info.com

Related Reports:

- Moldova: election outcome will test viability of Europe’s eastern expansion

- European taxpayers pick up bill for Ukraine crisis

- Will Europe’s Eastern Partnership survive the Kremlin’s confrontation with Brussels?

- EU’s new climate-change targets will drive industry towards US and China

www.geopolitical-info.com