Sanctions on Russian banks and its energy companies are beginning to have a long-term impact on Russia’s economy. Vital foreign investment and access to sophisticated Western oil industry technology have been cut off. This is beginning to hit Russian energy giant Rosneft and its ambitious exploration plans. Energy companies can hold out for two to three years, but their exploration and export plans will be curtailed and could hit Russia’s social-political stability in the mid- and long-term.

Wide-ranging sanctions imposed on Russia by the United States and the European Union for annexing Crimea and destabilising Ukraine’s eastern regions are hitting home. Access to foreign technology has been frozen and Western companies banned from cooperating in Arctic, shale oil and deep water drilling projects. The sanctions are designed to damage Russia’s oil production, which provides 80 per cent of Russia’s energy export revenues and 40 per cent of its state budget. Russian energy giant Rosneft’s ambitious expansion plans to double oil and gas output are jeopardised. China cannot replace the cutting-edge technology provided by the West. This will hamper and delay Russia’s future oil projects and hit government revenue in the mid-term perspective.

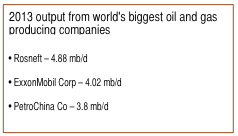

RUSSIA, the world’s second-largest oil producer after Saudi Arabia, provides more than 13 per cent of the world’s oil. Its oil production in 2014 is forecast to remain stable at around 10 million barrels a day (mb/d), but is not expected to grow much in the future, although Russia’s energy ministry hopes to increase it to 11 mb/d by 2030.

But many experts expect production to decline by 2015 – 2016 even though Russia has oil reserves three times greater than the US, and the world’s biggest technically recoverable ‘tight’ oil resources of up to 75 billion barrels in the Bazhenov field.

Blocking technology

Development of many new projects has been delayed and peak production targets have been repeatedly revised down. Moscow’s hopes of achieving 440,000 b/d from its shale oil production by 2020 are becoming increasingly unrealistic.

Russia and its biggest oil producer Rosneft are dependent on expertise from the US and other Western countries to exploit their costly tight oil reserves and other hard-to-recover reserves in the Arctic. These could hold up to 30 per cent of the world’s remaining undiscovered oil and gas. Rosneft wanted to invest US$400 billion in Arctic oil extraction using help from Western companies which account for almost half the technology needed in hard-to- recover oil projects and 80 per cent used offshore. Energy sanctions imposed on Russia by the European Union and the US are blocking the export of these cutting- edge technologies for oil fields in shale plays, the Arctic and deep-water oil projects.

The sanctions are hampering the development of Russia’s new unconventional oil reserves, assumed to be the world’s largest, and have discouraged Western banks from financing new Russian energy deals. Existing deals are unaffected.

Access to banking

Half a dozen of Russia’s biggest state-connected banks, accounting for more than half its banking assets, have been cut off from Western financing. Russian banks and companies have to repay US$134 billion in external debt between now and the end of 2015. Russian oil and gas giant Rosneft alone has to repay US$32 billion in foreign loans. Russia risks losing US$500 billion in direct investment with a multiplier effect of another US$300 billion, and a revenue loss of US$27-65 billion in the mid- term perspective, according to the US banking company Merrill Lynch.

Western sanctions are hampering Rosneft’s ambitions against a background of falling oil prices from US$110 to less than US$80 per barrel. Its chairman Igor Sechin, a close ally of President Vladimir Putin and the kingpin in the Russian oil industry, has been blacklisted by the US Treasury and faces personal sanctions.

Rosneft is the world’s largest publicly traded oil company by output and reserves. It had proven hydrocarbon reserves of 33.01 bb of oil equivalent at the end of 2013, and is producing almost 5 mb/d – four per cent of global supply – more oil than OPEC members Iran and Iraq.

Corrupt country

Rosneft’s rise began in 2004 when Igor Sechin was appointed by President Putin after Rosneft’s takeover of the main assets of Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s Yukos Oil Co, Russia’s largest crude oil producer. Mr Khodorkovsky was jailed in 2003 and spent 10 years in prison camps on tax evasion and fraud charges. Russia’s investment climate or corruption did not improve when the energy sector returned to state control. Russia is the most corrupt nation among the G20-group of advanced economies and ranked 127 out of 183 countries in the 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index of Transparency International. Igor Sechin became the CEO of Rosneft in May 2012 after initiating the sacking of Rosneft’s previous boss Sergei Bogdanchikov, a lifelong oilman. Mr Sechin orchestrated Rosneft’s US$55 billion enforced purchase of TNK-BP, a BP oil joint venture in Russia, which made Rosneft the world’s largest listed oil producer by far. Mr Sechin became the second most powerful figure in the Kremlin and the leading exponent of Mr Putin’s determination to restore the state’s role in the Russian economy.

Rosneft’s expansion

Together, Mr Putin and Mr Sechin used Rosneft and their acquisition policies to restore state control in the Russian oil sector. Rosneft is now 69.5 per cent government owned and controls about 40 per cent of Russia’s total crude oil output.

Rosneft’s annual revenue increased 128 per cent to an estimated US$143.6 billion between 2010 and 2013. The share of state-owned enterprises accounted for more than half of Russia’s GDP after Rosneft’s acquisition of TNK-BP in March 2013, compared with just 30 per cent in 1999. Within the next two decades, Rosneft plans to launch 10 new oil fields and double its total oil and gas production to 10 million barrels of oil equivalent per day – more than the current production levels of BP, Shell and Chevron combined.

Rosneft is now trying to acquire Basneft, a ‘private’ oil company, owned by oligarch, Vladimir Yevtushenkov with a personal wealth of US$7.5 billion. He has been charged with illegal privatisation and money laundering. His legal troubles are expected to disappear if he sheds his company.

Acquisition strategy

Rosneft also plans to double gas production to 100 bcm by 2020 to become Russia’s second-largest gas producer after Gazprom. Rosneft increased gas production by 132.9 per cent from 16.39 bm in 2012 to 38.17 bcm in 2013. The company’s share of Russia’s gas market rose from 3.9 per cent to 8.8 per cent. The production increase is primarily through an acquisition strategy. It has consolidated its grip of the Itera gas company and bought a 51 per cent stake in Sibneftegaz, capable of producing 12 bcm per year, with the potential to increase to 18 bcm/y. Rosneft’s gas reserves at the end of 2013 were 6.6 trillion cubic metres (tcm). It accounts for 32 per cent of Rosneft’s hydrocarbon reserves and accounted for almost 10 per cent of the company’s production. But Rosneft’s oil and gas ambitions, particularly its supply agreements with China, depend on transport rivals, Gazprom and Transneft. Rosneft has criticised both companies, which have an infrastructure monopoly, for imposing their own goals and interests at a cost to the entire energy industry and Russia’s economy. Mr Sechin wants to abolish Gazprom’s export monopoly by reforming the gas sector. A first stage proposes an equal-profits price with equal domestic and export prices to give all Russian market players equal access to Gazprom’s gas transportation system. A second step would see Gazprom’s gas transport system becoming a state-regulated independent company, setting up a gas exchange and giving all market participants an opportunity to export gas. Gazprom would no longer be Russia’s sole gas exporter under this plan. Currently, around 27 per cent of Russia’s gas market is in the hands of ‘independent’ gas producers such as Rosneft, Novatek and others. Russia’s Ministry of Energy produced a draft energy strategy in January 2014 forecasting to 2035. This also proposed separating Gazprom’s gas transport business from production. Gazprom has resisted all proposals to relinquish its monopoly and is also fighting the EU’s attempts to liberalise the European gas market.

Historic deal

Exports are the most lucrative segment of Russia’s energy companies. Rosneft is also trying to acquire a stake in Transneft’s oil pipeline monopoly to gain control over the pricing of oil transportation via the ESPO-pipeline to China. Transneft is resisting this move.

Rosneft is also demanding access to Gazprom’s planned ‘Power of Siberia’ gas pipeline following a historic gas deal between Russia and China in May 2014. The Power of Siberia pipeline is estimated to cost up to US$46 billion. Rosneft wants to link building Gazprom’s new 38 bcm/y pipeline with its own new gas fields.

The Russian government has made no final decision about breaking the transport monopolies of Gazprom and Transneft.

But Western sanctions are forcing greater cooperation between Gazprom and Rosneft.

Rosneft has gained access to Western technology and management expertise by acquiring Yukos and TNK-BP. Rosneft’s crude oil production grew by an annual average of more than 3.5 per cent between 2009 and 2012 compared with TNK-BPS’s 1.5 per cent. But Rosneft’s growth was largely down to its close government ties to new resources such as the Vankor oil field in Siberia – Russia’s biggest oil find in 25 years. This started oil production in 2008 and accounts for almost 10 per cent of Rosneft’s total production.

Rosneft obtained part-ownership of ExxonMobil projects in Alaska, the Gulf of Mexico and US shale oil fields in 2011. The US government has called a halt on any work on the Sakhalin 1 project.

Western sanctions are also hampering Russia and Rosneft’s ambitious LNG export plans in Sakhalin and Vladivostok as nobody in Russia is producing parts for LNG export terminals. The sanctions ultimately threaten Rosneft’s and Gazprom’s entire eastern diversification strategies.

Chinese partnership

Rosneft has to work with BP, which has a 20 per cent stake in Rosneft, Statoil, Shell, SeaDrill – the world’s biggest offshore drilling company, Total and ExxonMobil in a series of bigger projects in Russia’s Arctic region. But joint LNG projects and exploiting its huge tight oil resources are hampered by the lack of drilling infrastructure and high costs.

The lack of access to foreign capital and financing for Russian companies and lenders is happening at a time when they have to re-pay US$134 billion in foreign debt by the end of 2015.

Russia and Rosneft have said they will expand and deepen their energy-technology partnership with China to replace dependence on Western technology and financing. China became Russia’s top trading partner in 2011, replacing Germany. Rosneft faces huge debts following the TNK-BP takeover but signed a US$70 billion pre-payment agreement with China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) in exchange for supplies in January 2014. It had previously signed another provisional US$85 billion oil supply agreement with Petrochemical Corp for 100 mt of crude over 10 years in October 2013.

Circumventing sanctions

These advanced payments provide Roseneft with important revenue but critics say they limit Rosneft’s oil exports to other customers who could pay higher prices. China may step in with financing and be able to support energy and other projects with pre-paying and other forms of closer cooperation, but this has limits and geopolitical risks. China will ultimately follow its own strategic interests which will try to play the West and Russia against each other to achieve the most profitable outcome. China also lacks cutting-edge offshore and hydro-fracking drilling technology and the oil service and management expertise. Russia and some Western companies may try to circumvent Western sanctions by playing the China card, finding legal loopholes and exporting technologies and equipment through third-party countries. But it will be impossible to halt Russia’s decline in production from mature fields without new exploration projects offering a return of at least 160 mt per year in the next few years.

Projects delayed

To achieve this, Russia needs to triple investment in exploration, but Russian companies lack sufficient funds and will need US$1.5 billion a year in foreign capital. Western sanctions are clearly hampering ambitious expansion plans by Rosneft and others. A planned US$2 billion deal between Rosneft and Vitol – the world’s largest independent oil trader, has been shelved because of the sanctions. This money was originally to have been raised from US and European banks.

Companies across the Russian oil industry have reduced capital spending and delayed important projects. Rosneft, which had built up a US$20 billion safety net on its balance sheet, has asked the Russian government for US $48 billion to buy its debt from Russia’s National Wealth Fund. The wealth fund was earmarked to support its pension system but the cash will be used now to off-set Western sanctions.

The Russian government is willing to support its energy champions in the short-term but this may undermine its future economic growth strategy and its social-political stability and its claimed ‘great power’ status.

Western sanctions, aimed at changing Russia’s short-term policies in Ukraine by imposing mid and long-term costs, are significant for Russia’s future economic growth strategy and social-political stability.

Russia may be able to muddle through the next two to three years, but its growing structural problems are tied to energy and banking sanctions and falling oil prices. The sanctions may have helped to deter Russia’s aggression in Ukraine in the last few months.

Russia’s new partnership with China is understandable and highlights Russia’s new geopolitical vulnerabilities and weakness. Russia hopes to expand its bilateral trade with China from about US$90 billion in 2013 to more than US$100 billion in 2015 but this will account for just two per cent of China’s global trade. Russia’s bilateral trade with the European Union is US$440 billion and represents half of Russia’s imports and exports.

Russia’s pivot to Asia will not solve its major structural problems of declining foreign investments, high-tech Western transfers, capital outflow and corruption. GDP is stagnating, if not declining, and is hit by Western sanctions and falling oil prices.

The Kremlin has launched a 10-year defence spending programme and allocated US$77 billion for the first year. It has also said it would meet social spending promises. Now it has to decide again between ‘guns and butter’.

Mr Putin’s Ukraine policies appear increasingly self- defeating in this perspective, by weakening the very economic-political foundations on which Kremlin power and Russia’s future relies.

This report has been written by Dr. Frank Umbach and made available to our members through the courtecy of © Geopolitical Information Service AG, Vaduz

http://www.geopolitical-info.com/en/

Related Reports:

- Speaking at a Difficult Time: Sechin in Berlin

- Ukraine: peace plan fails as eastern region becomes a frozen conflict

- The geopolitical impact of falling oil prices

- Sanctions – Russia fends off damage to economy with deep spending cuts

![]() © Geopolitical Information Service AG, Vaduz

© Geopolitical Information Service AG, Vaduz

www.geopolitical-info.com