Healthcare in Europe has been a flag-bearer in developing new drugs and medical care to create the world’s healthiest and longest-living society. But it comes at huge cost to public funds. Countries throughout the European Union are now looking at new ways of reforming the way healthcare is provided and run. Harmonising healthcare across EU countries is one way while another could be greater provision of privately-funded high-quality healthcare.

EUROPEAN healthcare systems have helped create the world’s longest-living and healthiest society. But these systems are also the most expensive in the world. Germany spends 11 per cent of GDP on healthcare, with around 77 per cent being funded by the public sector. Rising healthcare costs, with an ageing population and an increased rate of chronic diseases, have led to continuous attempts to reform healthcare delivery in all European Union member states.

The diverse heritage of European healthcare systems and their dependence on public financing make reforms a highly emotional topic of public debate.

Little convergence

The EU has issued guidelines in an effort to harmonise healthcare systems across its member states. This should make it easier to control costs, launch novel therapeutics with European legislation and make better use of the capacity of hospitals and health services across all borders.

In an analogy with social welfare guidelines, however, healthcare regulation in Europe lies exclusively within the authority of each country. There is little convergence of European health systems and policies so far.

To launch a new drug on the market – with the exception of orphan drugs or rare-diseases therapeutics – consent has to be obtained from every country’s own drug agency. Reimbursement for those therapeutics are also a national matter, as is the market registration for generic drugs or doctors’ licences.

Pharmaceutical companies and healthcare organisations face a far more complex and costly market entry procedure in Europe than the US. One health economist from a leading pharmaceutical company said, ‘It’s like conquering territory castle by castle…’.

Each EU member state may apply different criteria to drug approval, most of which include therapeutic and economic parameters. And European countries operate at varying speeds.

The EU recommendation of post-market surveillance of therapeutics – standard in the US for better risk control of drugs – has only been introduced in two EU countries, the UK and Germany.

Living longer

The latest data on health and health systems for 35 European countries, presented by the European Commission (EC) in cooperation with the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in February 2015, included all European Union members, candidate countries and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) members. The data reveals the aftermath of the 2009 economic crisis and the impact of subsequent healthcare spending cuts:

Life expectancy continues to increase in the EU, reaching 79.2 years on average in 2012 (82.2 years for women and 76.1 for men) – an increase of 5.1 years since 1990.

However, inequalities persist with a gap of 8.4 years between the highest and lowest member states. Infant mortality in Greece, for example, is on the rise while life expectancy decreased in the last two years to levels typically seen in developing countries – an observation which is largely attributed to the breakdown of public services following the financial crisis.

Health spending in real terms – adjusted for inflation – decreased by 0.6 per cent per year, on average, between 2009 and 2012. This was due to cuts in the health workforce and salaries, reductions in fees paid to health providers, lower pharmaceutical prices, and self-payments made by patients.

Excessive bureaucracy

Containing costs has focussed historically on the highly profitable pharmaceutical industry and its therapeutic products, which only account for 15-20 per cent of the average European healthcare budget.

Policymakers have shifted their focus only recently to the main cost drivers in healthcare, which are the hospital services and the management of chronic diseases. Comparative data also shows that a monopoly of public health insurance, like the ‘Gebietskrankenkassen’, the regional health insurance in Austria, with its excessive bureaucracy, is much more costly and rigid than privately managed health insurance schemes.

This is one of the reasons why Switzerland voted in 2014 against the introduction of a uniform public health insurance system replacing its current private insurance scheme.

Waiting times

The number of doctors per capita – a measure of the accessibility of care – has increased since 2000 in all EU countries except France, where it has remained stable. The number of practising nurses has also increased in all but two EU member states. This is mainly due to a trend of moving patients from costly hospital care to day care at home.

Waiting times for non-emergency surgical interventions vary widely across EU countries. Some have made progress in reducing waiting times over the past few years, while in others such as Portugal, Spain and Greece, they have started to rise. This is probably the result of surgeons leaving those countries for better pay and facilities abroad.

Patients, too, are increasingly crossing borders within Europe to obtain medical treatment. Both imports and exports of healthcare services have grown in most EU countries between 2007 and 2012.

Increasing obesity

Patient mobility in Europe may see further growth as a result of the EU directive on cross-border healthcare. This supports patients exercising their right to cross-border healthcare and promotes cooperation between health systems.

The EU actively promotes and advises on association agreements between EU members, and bilateral agreements with its neighbours, in an effort to harmonise rules and build capacity in the field of public health.

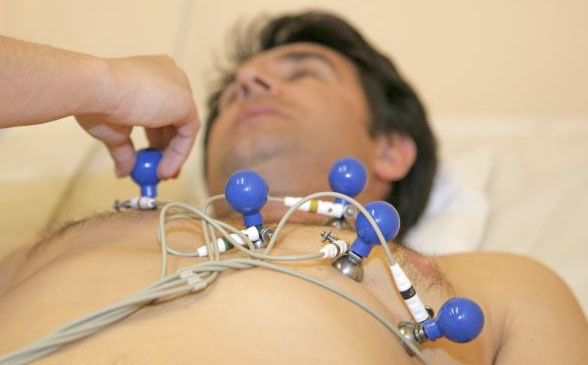

(photo: dpa)

Overweight and obesity is increasing in the EU which now records 53 per cent of adults as either overweight or obese.

Obesity, which presents even greater health risks than being overweight, currently affects one in six adults or 16.7 per cent in the EU. This has increased by more than a third in 10 years. However, there are considerable variations between countries and obesity is mainly a problem among the lower income population in an otherwise rich society.

High costs

EU healthcare policy today focusses on malnutrition, physical inactivity and the prevalence of chronic diseases, such as diabetes, which are all typical symptoms of an affluent society. Increasing cost-pressures on healthcare structures and a more challenging European economy mean this focus could shift to curbing the rise of cardiac diseases or psychological and behavioural disorders. No European country seems entirely happy with its healthcare system, but radical reforms are unlikely or advisable. An OECD analysis of healthcare systems across the globe locates no ‘winning’ criteria for the cost-benefit ratio or patient satisfaction. Reforms typically lead to high costs in introducing change while the long-term benefit is not obvious for European policymakers or patients. But some countries have initiated change. Experts believe these could make healthcare more efficient and spark similar positive initiatives across the EU. Germany’s government subsidises so-called ‘integrated care’, a patient-centric – as opposed to a therapy-centric – approach to healthcare insurance.

Costly ‘doctor hopping’ or gatekeeping to specialist care is minimised which improves cooperation among specialists to diagnose and treat complex, but widespread, disease and health issues such as migraine.

Private initiatives

Denmark is investing in a system of electronic patient records. Incentives and regulations have been implemented to link with the existing electronic patient system rather than creating a single new one. The results include lower treatment costs, reduced paperwork and improved quality of care.

The UK is systematically measuring and analysing the outcomes of medical interventions and treatment. Data gathered on heart surgery has already helped cut mortality rates by half.

An initiative to gather Patient Recorded Outcomes Measures (PROMs) could change how doctors view the success of procedures which could improve the quality of care and reduce costs. The EU will need to do more than just provide guidelines. National systems have to be prepared to meet a variety of challenges looming in the near future.

Although all countries started with different histories, they all face the same cost-and-efficiency problems. New thinking and Europe-wide strategic plans are required to avoid recycling old arrangements which have proved to be ineffective.

But implementation of new policies will continue to lie with local politicians. Rather slow political processes limit adapting current healthcare systems, in particular when budgets are tight. The result is that private initiatives could become more important.

More of the weight and cost of European healthcare systems will have to be assumed by the private sector and for-profit organisations. But access to high-quality healthcare for all may be at risk with an increasing private sector influence, and socio-economic inequality unavoidable.

This report has been written by Dorothee Deuring and made available to our members through the courtesy of © Geopolitical Information Service AG, Vaduz:

www.geopolitical-info.com

Related Reports:

- Beware of false hopes Quantitative Easing can offer Europe

- Cheap oil and weak euro could drive Europe’s growth

www.geopolitical-info.com