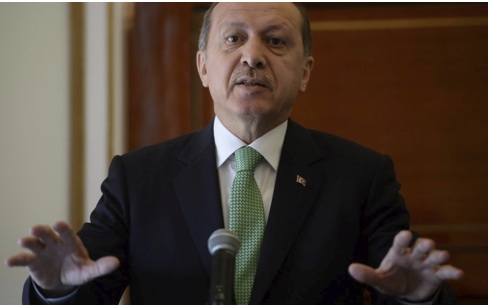

The central role of the state and its dominance over society are key factors in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s plans for a ‘New Turkey’. Mr Erdogan, who became the nation’s first publicly elected president in August 2014, must overcome protests against his autocratic rule, continue negotiations with the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) and deal with the issues caused by conflicts in neighbouring Syria if he is to complete his project by 2023, when the nation celebrates its centenary.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan is the first Turkish president to be elected directly by the people. He believes that gives him a far-reaching mandate. Mr Erdogan is pursuing a project under the slogan ‘New Turkey’ to profoundly transform the Turkish republic. His ambition is to make the country into a Muslim regional power and the world’s tenth strongest economy by 2023, the centenary of the foundation of the Turkish republic. His plans have polarised politics and society. Though he still has the backing of the majority of Turks, internal tensions have increased. The Kurdish question remains potentially explosive. The presence of 1.5 million refugees from Syria is meeting with growing resistance. Whether the AKP secures a two-thirds majority in the general elections in June 2015 will play a decisive role in Mr Erdogan’s political future. If it does, he could strengthen his long term position by passing a new constitution.

RECEP Tayyip Erdogan was Turkey’s prime minister for more than a decade, but since becoming its first publicly elected president he has made it very clear that he regards his new role as the one that counts.

He chaired a cabinet meeting in early 2015. That was a demonstration of power; though he is constitutionally entitled to do so, previous presidents have only exercised that right in times of crisis.

He sees his direct election by the people as signalling that the president, not the prime minister, is head of the executive. Mr Erdogan will seek to secure a two-thirds majority for his Justice and Development Party (AKP) in the general elections in June 2015, which would enable him to pass a new constitution to bolster the powers of the president as he desires.

His election in August 2014 marks a profound change in the nation. He announced even before the polls that he would create a ‘New Turkey’. Ever since the victory of the AKP, which he founded, in the general elections in June 2011, he has gradually shown what this will look like:

• It is outwardly Islamic. Mr Erdogan has propagated a conservative view of the Turkish family in numerous speeches. The ban on the headscarf in public places has been removed and women are urged to exhibit ‘Islamic’ conduct. The sale and consumption of alcohol will be restricted. A large new mosque on the east bank of the Bosphorus is intended to demonstrate the role of Islam in Turkey

Hot topics

• It sees itself as the successor of the Ottoman Empire. The history of the great sultans is presented in the media, and history syllabuses have been changed accordingly. The ‘Ottoman’ (Arabic) script is increasingly being taught in schools. The colossal presidential residence which Mr Erdogan inaugurated in October 2014 is intended to recall the palaces of the Seljuq dynasty of the 11th to 14th centuries

• It will become the leading power among the Islamic states of the Middle East. The prospect of Turkey acceding to the European Union has lost appeal. The question of Palestine and relations with Israel will become hot topics of its foreign policy

• It will become the world’s 10th biggest economic power. A series of large projects – including Istanbul’s new major airport, which is planned to be the world’s largest, a third bridge over the Bosphorus and a new waterway parallel to the Bosphorus – is designed to demonstrate that.

Erdogan’s rise to power

• Recep Tayyip Erdogan was born in 1954. His father was a coastguard in the Black Sea town of Rize and the family moved to Istanbul in 1967

• Biographers say he sold lemonade and bread rolls to help pay for his religious education

• While studying management at the city’s Marmara University he met Necmettin Erbakan, who later became Turkey’s first Islamist prime minister

• He played semi-professional football while at university

• Mr Erdogan entered a political career in the Islamist Welfare Party and became mayor of Istanbul in 1994

• In 1998 he served four months in jail after being convicted of inciting religious hatred by reciting a poem in public

• Four years later his AKP won a landslide general election victory, but at the time he was banned from holding political office

• The law was quickly changed and he became a member of parliament and, within days, prime minister

• Mr Erdogan has subsequently won two further elections, in 2007 and 2011

• He is a vociferous opponent of Israel – formerly a close ally of Turkey – and backs the Syrian opposition’s revolt against President Bashar al-Assad

Autocratic rule

The project is intended to be completed by 2023, when the Republic of Turkey celebrates its centenary. Mr Erdogan is following in the reforming footsteps of the nation’s founder, Kemal Ataturk.

He is aiming to transform what began as a secular national state into an Islamic state in political, social and cultural terms. The face of the ‘New Turkey’ will be different from that of the Kemalist republic, but continuity is sought in one key aspect of the political system: the central role of the state and its dominance over society.

Like Ataturk, Mr Erdogan identifies with ‘the state’, dismissing opposition and differing viewpoints as attempts to weaken it. He believes that the results of the general and presidential elections have authorised him to speak in ‘the name of the people’, marking the start of the shift towards an autocratic form of rule.

Islamic morals

Political developments in Turkey since 2013 have been marked by growing tensions between those loyal to Mr Erdogan and the opposition. The protests began in May 2013 in Gezi Park in the Europeanised Beyoglu quarter of Istanbul. They were sparked by the city government’s decision to carry out extensive building work which would have profoundly changed the character of the neighbourhood without consulting the public.

The local protests spread to other cities. They were targeted at the autocratic style of governing of the prime minister and the leading AKP figures, but above all against Mr Erdogan’s interference in the lifestyle of a section of society which is unwilling to bow to the Islamic morals which he proclaims. Security forces cracked down hard on the demonstrators and the president blamed the unrest on a foreign conspiracy.

The government only gradually revealed that it believed the protests to be a plot by the religious movement of the Islamic preacher Fethullah Gulen.

Former ally

Popular Islam has a centuries-long tradition in Anatolia, which comprises most of modern Turkey. When the AKP came to power in 2002, Mr Gulen was a popular figure among sections of society.

The esteem in which he was held was based not least on his engagement in the field of education. In the early years of Mr Erdogan’s rule, the Gulen movement was a welcome ally of the AKP in its fight against the judiciary and the military, which were dominated by Kemalists.

Following the election victory of June 2011, it became a potential rival in the struggle for power. Mr Erdogan decided to break ties with his former ally, who is now in self-imposed exile in the United States.

Recordings of telephone conversations purporting to reveal gross corruption by leading AKP politicians were leaked in December 2013, implicating not only several ministers, but also Mr Erdogan himself.

Press curbs

During raids, the police found incriminating materials on the suspects. The prime minister and the government-loyal press branded it a coup attempt. Instead of investigation, wide-scale repression was the order of the day. Hundreds of public prosecutors and other judicial and internal security staff were transferred or removed from duty. The government sought to prevent the issue from being reported in the press and social media. Though four ministers resigned, they were rehabilitated during 2014. Parliament decided in January 2015 not to bring them to trial. Mr Erdogan tirelessly recounted his version of events, arguing the scandal was orchestrated from outside by hostile and envious forces seeking to hinder the nation as an Islamic country on its path to future greatness as the ‘New Turkey’.

New constitution

The country presents a contradictory picture in 2015. On the one hand, at least half its population still backs Mr Erdogan. Indeed, his rule has boosted the self-confidence of many citizens; they have experienced a material improvement in their living conditions, which they credit to their new president.

The outcome of the 2014 election once again gave proof of that solidarity. Mr Erdogan will make every effort in the coming months to ensure he can cement his position by way of a new constitution, with the prospect of representing the ‘New Turkey’ at the centenary of the republic.

On the other hand, signs of instability are rife. The escalation of the crackdown marked the real start, rather than the end of the conflict with the Gulen movement and the political opposition. Will the AKP pursue it further? In the January 2015 vote on whether to send the four ministers to trial, around 30 ruling party MPs broke rank. The Kurdish question is as open as it has ever been. The peace process between the government and the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK), which is conducting an armed struggle for an independent Kurdish state within Turkey, has stalled.

Growing risk

Both sides are deeply mistrustful of each other’s intentions, especially as the government refuses to aid the beleaguered Kurds in the Syrian city of Kobani.

The conflicts in neighbouring Syria, and the presence of the Islamic ‘caliphate’ there, are increasingly making themselves felt in Turkey. The fact that 1.5 million refugees have been given what Mr Erdogan describes as ‘hospitality’ has met with concern and anger in parts of

the population. There is a growing risk that the clashes in Syrian society will be carried over to Turkey, including terror attacks. What will happen if Mr Erdogan does not achieve his project of a constitution which bolsters the position of the president in the ‘New Turkey’? The opposition parties have not yet managed to profit from the social tensions. Could divisions occur within the AKP?

Market collapse

Much will depend on Turkey’s future economic development, since the stability of ‘Erdogan’s system’ relies to a high degree on the strength of the economy. The low price of oil is currently improving the balance of payments. However, the country continues to import more than it exports, and Turkish products are competitive only to a limited degree. Moreover, some markets in the Middle East have collapsed. Foreign investments are already on the decline, a trend which will be exacerbated by sustained political instability and legal uncertainty. The efforts of the government, and of Mr Erdogan himself, to influence the decisions of the central bank do not bode well in that respect. Worsening of the economic situation, however, would impact negatively on the support for the president. The question then would be whether change would come about within the party system, or whether there would be increasing unrest on the streets.

This report has been written by Prof. Dr. Udo Steinbach and made available to our members through the courtesy of © Geopolitical Information Service AG, Vaduz:

www.geopolitical-info.com

Related Reports:

- Erdogan’s presidential win brings hopes and fears to Turkey

- The rise of the Kurds could define new shape of Middle East

- Dispute with Turkey casts shadow over Cyprus gas bonanza

- Turkey’s elections will give pointer to its future

- How ISIS is shifting relationships in the Middle East

www.geopolitical-info.com