By Philipp Schröder

When in July 2016 Theresa May took office as Prime Minister, she assured the world that “Brexit means Brexit” and said she was determined to “make Brexit a success for Britain”. Whether she can achieve this ambitious goal will largely depend on the kind of trade relationship her government can secure with the EU.

Thorough preparations required

The Brexit vote is causing a period of profound uncertainty about the future EU/UK relationship. The EU treaty foresees a period of two years for exit negotiations once Article 50 has been invoked. Theresa May made it very clear that her government will only trigger Article 50 once it has prepared a negotiation strategy, and that such a strategy will also need to be backed up by major stakeholders such as the regional governments of Scotland and Northern Ireland.

The British government will have to ponder carefully when to trigger the exit mechanism. This is a critical decision of enormous tactical relevance. Should the two year negotiation period expire prior to concluding and ratifying a deal with the 27 remaining EU countries, the UK risks losing its trading privileges and default back to WTO trading rules. This could have severe and adverse consequences to the UK economy.

In a recent study the OECD estimates that trade in goods was 60% higher between countries in European Economic Area (“EEA”), which benefit from full access to the single market, than if trading partners had simply relied on WTO rules.[1] An analysis of the British Treasury comes to a similar result, estimating a 73% differential for trading in goods and a 16% differential for trading in services.[2]

Miriam González, wife of former deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg is one of the very few experts in international trade law based in London. She recently pointed out that the UK government has yet to decide on a relationship model before it can even begin defining its strategy, priorities and trade-offs for the upcoming negotiations. This means the exact timing of invoking Article 50 continues to remain uncertain.

The bone of contention

Finding a suitable path for resolving the obvious conflict between continued access to the European single market and the UK’s desire for stronger immigration control will be the main issue of the upcoming negotiations. The UK’s lack of control over EU workers’ migration in particular played a key role in the referendum.

Free movement of workers was relatively uncontroversial in 1973 when the UK joined the European Economic Community (“EEC”) as standards of living did not diverge too far. Since the enlargement of the EU to Eastern Europe, the topic has turned controversial due to the high influx of Eastern European workers. Their lower standard of living put pressure on wage levels and led to crowding out lower income jobs. The futile promises David Cameron gave earlier to curb EU migration turned into a major handicap for his Remain campaign.

Nevertheless, the EU remains adamant and insists on the “four freedoms of the single market”, namely the free movement of goods, services, capital and labour (i.e. people), in return for full access to the single market. Donald Tusk, President of the EU Council, recently affirmed “There will be no single market á la carte”.

But why should the free movement of people be such an inherent and indispensable condition for the European single market, a condition that cannot be negotiated away?

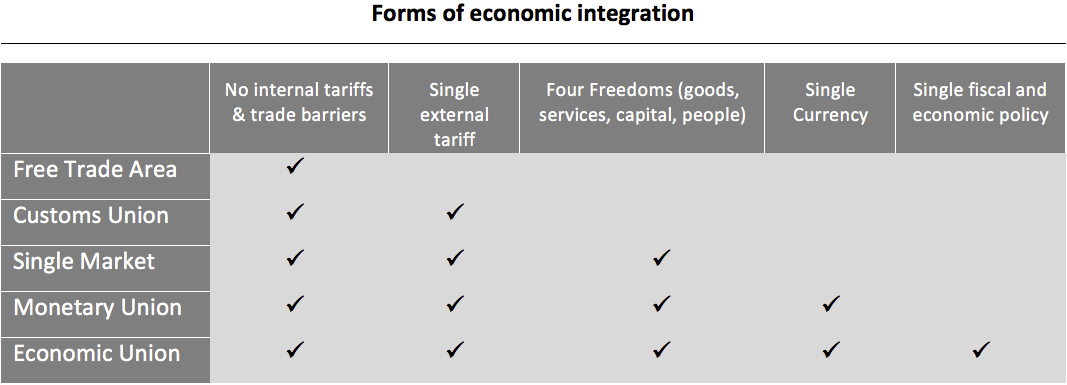

Economic integration among a group of countries comes in a variety of different forms. WTO rules in principle simply ensure that member countries cannot treat any one country less favourably than any other. Therefore, the tariff that applies to the so-called Most Favoured Nation (“MFN”) must apply to all countries. As a result tariffs are not necessarily abolished but rather unified.

The simplest form of a Free Trade Area (“FTA”) merely reduces or abolishes tariffs and import quotas between two groups of countries. The next form, a Customs Union, additionally imposes joint single external tariffs towards non-participating countries.

More sophisticated FTAs such as the currently negotiated Transatlantic Trade and Investments Partnership (“TTIP”) with the US or the concluded but not yet ratified Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (“CETA”) with Canada do also cover a much wider range of policies such as foreign investments, mobility of staff, investor-state dispute settlement, technical barriers, consumer rights, IP protections, and government procurement, etc.

The EU has established over 50 FTAs, amongst others with South Korea, Chile, Mexico, South Africa, etc., and Turkey is part of a customs union with the EU.

A single or common market represents a much deeper form of economic integration than even a sophisticated FTA. It encompasses the movement of goods and services free of tariffs and non-tariff barriers as well as the free movement of the economic production factors – capital and labour in particular. Importantly, a fully functioning single market requires a common regulatory framework as a prerequisite to ensure fair internal market conditions.

In a single market standards and regulations are not simply reciprocally accepted, as in a sophisticated FTA, but rather harmonised thereby guaranteeing a “level playing field” for all market participants. This is the reason why there is a need for an intense harmonisation endeavour and joint regulation such as common product liability laws, a common anti-trust and competition policy, or a common trade policy with third countries – just to name a few. The common regulatory framework creates certain subsidiary requirements, such as common standard setting bodies and judicative court institutions. Similarly, free movement of people also demands intensive co-operation on cross-border crime as well as justice and home affairs, etc.

If free movement of labour becomes restricted, e.g. by granting only temporary work permits, the single market effect cannot unfold in its entirety. For instance, it may still be possible to relocate production plants with a temporary work force. But would it be feasible to relocate an entire enterprise, including its headquarters and management team? Or could one move the R&D department and have its human and intellectual capital work as effectively as if full freedom of movement were granted? Restricting partially the free movement of labour would violate the level playing field principle.

The above shows the degree of interdependence between the free movement of people and a fully functioning single market. Participating in a single market requires some political integration beyond the economics and trade terms.

Is a new bespoke trade model a realistic option?

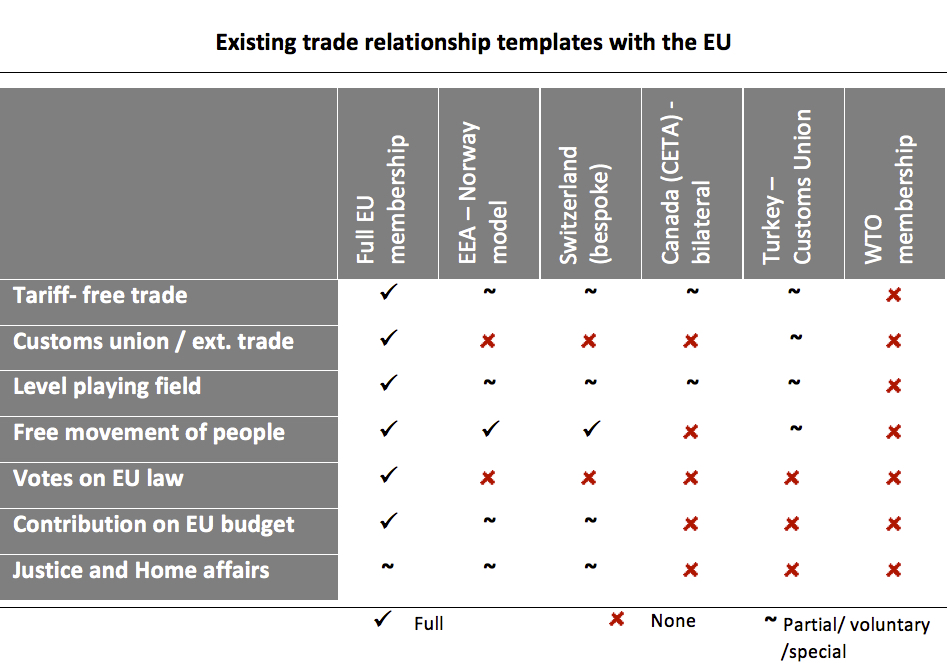

Although there are a number of existing trade relationship templates with the EU, none of them represents a satisfactory solution for the Brexiteers’ objectives. Consequently, the UK is likely to aim for a made-to-measure trade pact with the EU which would optimise its position on single market access and immigration control.

The option to fully participate in the European single market for a non-EU member is the EEA or the so-called Norway model. The EEA grants full access to the European single market in exchange for a contribution to the EU budget, acceptance of the four freedoms, and implementation of several EU rules albeit without voting rights on single market affairs. While bilateral trade agreements e.g. with Canada and Turkey fall significantly short of the full single market, Switzerland has achieved a relatively similar result as Norway by way of several detailed bilateral deals.

Although the Switzerland model is somewhat less comprehensive than the Norway model – e.g. the financial services industry is exempt – the Swiss had to accept all four freedoms of the single market in full.

In a referendum in 2014, the Swiss voted to introduce EU migration quotas from 2017. As a response, the EU has threatened to suspend all trade agreements currently in place with Switzerland under the so-called “guillotine clause”. The Swiss/EU dispute over the free movement of people could be a litmus test for a potential bespoke deal with the UK.

When trying to forge a bespoke deal, the UK will undoubtedly face a number of issues.

First, negotiating a trade deal consumes a tremendous amount of time. The recently agreed CETA deal with Canada took about seven years until its conclusion. Not only is the EU entangled in bureaucracy, but Canada also had to align differences among its own provinces. For the Swiss deal, both sides had to agree 20 principal agreements and 100 supplemental accords over a time span of roughly 10 years.

The closest precedent to Brexit so far is Greenland, which as an autonomous overseas territory of Denmark departed the EU in 1985. The Greenland exit negotiations took about three years. It is probably a fair statement that these negotiations were much simpler given the only subject of significance was fishing rights.

Once negotiations have been concluded, the new deal with Britain will require ratification by all 27 members’ states. This is going to add significantly more time on top of the period it took to negotiate the agreement in the first place.

Second, a made-to-measure trade deal is difficult to reconcile with the current EU position, which is objecting to a single market à la carte. EU member states eyeing to follow the UK’s example shall not be tempted by an enticing precedent. To make matters worse, the EU negotiation position will not be a homogenous one. The 27 remaining EU countries exhibit a wide-ranging diversity of different sensitivities and priorities.

Directionally, the lower the relative economic exposure to the UK on the one hand and the higher the domestic anti-EU sentiment on the other hand, the less accommodating an EU country will be towards the UK’s negotiation position. Judging by that measure, EU-heavy weights France and Italy together with Poland, Hungary and Greece will likely tend towards the less accommodating camp. Germany and Ireland, by contrast, should be able to take a more constructive bearing.

Third, the UK’s institutional capacity to renegotiate a customised deal is questionable given the scarcity of seasoned trade negotiators and lack of experience in concluding bilateral trade negotiations. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that the UK will need to strike its own deals with third countries whose trade relations to date were covered by EU agreements. This means negotiating more than 50 new trade agreements. Liam Fox, the new international trade secretary might be tempted to poach British nationals from the EU Commission and WTO to staff up his new ministry.

Negotiating a comprehensive and tailored trade treaty is a colossally complex and lengthy challenge. Not only will Britain run the risk of not finishing within the two years defined by Article 50 and defaulting back to WTO rules, but it will also incur severe economic damages given the lingering uncertainty in the meantime. Time will be of the essence, especially as leverage will increasingly gravitate towards the EU the closer the 2 year negotiation period draws to an end. Furthermore, the timing of the upcoming general elections in France and Germany in 2017 is not in Britain’s favour. It can be expected that the EU will not make any decisions of importance until then.

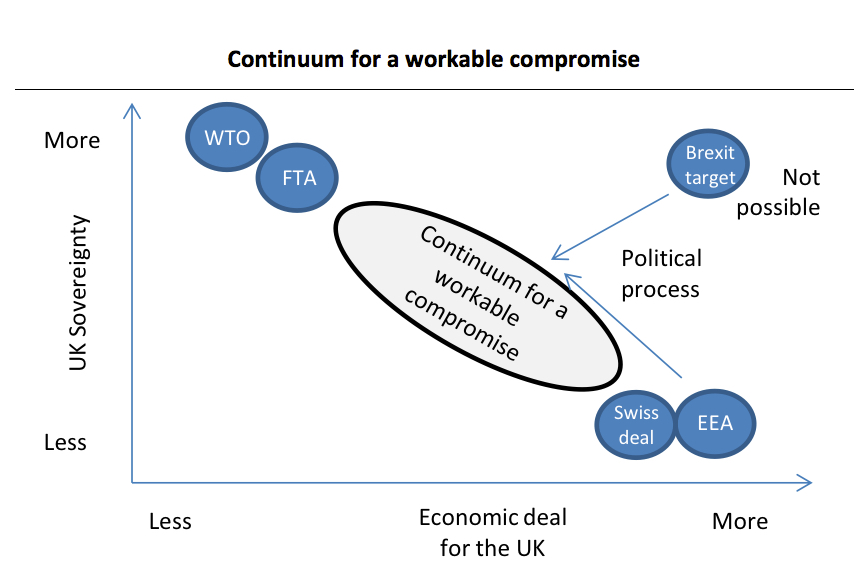

Finding a workable compromise

An ideal negotiation outcome should simultaneously achieve (i) the containment of short term economic uncertainties, (ii) rebalancing the negotiation power by alleviating the time pressure of Article 50 and (iii) provide sufficient time to elaborate a mutually agreeable permanent trade relationship. The longer the negotiation window, the greater the likelihood that the ultimate deal will be beneficial for all parties given the sky-scraping complexities at stake.

An extension of the negotiation period beyond the 2 years according to Article 50 would obviously be an option. Achieving this, however, should prove challenging given the need for an unanimous agreement by all 27 EU countries. The EU will not find it easy to concede such an extension as it would mean relinquishing negotiation leverage without receiving a tangible benefit in return. Furthermore, such an extension would not put an end to the continuing economic uncertainties.

Another possibility could be a staggered Brexit. The UK could initially fallback to the readily available “off the shelf” EEA (Norway model) as an interim arrangement. Britain would need to apply for EFTA (Norway, Iceland, Lichtenstein) membership, but given the interim nature, this should be manageable without re-designing the EFTA’s institutional set up. Via the EEA, Britain would initially retain full access to the European single market. It would have the advantage of pursuing its own international trade treaties, which was another central theme of the Leave campaign. The UK would – a welcome effect – also be excluded from the common agricultural and fisheries policy, common foreign and security policy as well as justice and home affairs.

In order to accomplish an agreeable as well as an enduring trade and immigration solution, a roadmap would need to be agreed. This roadmap should include the following cornerstones: (i) a limited and specified time span to conclude the negotiations in e.g. 5 or 7 years, (ii) an action plan with defined milestones, (iii) a clear and transparent communications policy during the negotiation period, and (iv) a definition of the targeted trade model pertinent to providing visibility on the final destination.

A potential permanent solution could for instance be represented by an increasing economic integration in a number of selected industries of high trade significance to both parties, e.g. financial services, automotive, pharmaceuticals, food and beverages. The higher the desired intensity of the economic integration in a specific sector, the more the four freedoms would have to be respected in that sector, including the adherence to relevant harmonisation efforts. Trade in other sectors would have to be based either on WTO rules or on a more comprehensive trade arrangement compatible with a higher degree of immigration control.

A potential permanent solution could for instance be represented by an increasing economic integration in a number of selected industries of high trade significance to both parties, e.g. financial services, automotive, pharmaceuticals, food and beverages. The higher the desired intensity of the economic integration in a specific sector, the more the four freedoms would have to be respected in that sector, including the adherence to relevant harmonisation efforts. Trade in other sectors would have to be based either on WTO rules or on a more comprehensive trade arrangement compatible with a higher degree of immigration control.

Cherry picking the most attractive sectors for a more intensified economic collaboration will not work for either side. The eventual solution would need to be a mutual compromise and the path towards it a political process – for both sides.

The above mentioned two-step approach would present a tough challenge to accept for all those hardliner Brexiteers who were seeking a rigorous and fast exit.

However, even the EU needs to find its balance. On the one hand, there is a strong incentive to preserve existing trade and investment links since the UK is an important partner for the EU as a whole as well as for many individual countries. On the other hand, the EU must avoid moral hazard which favours a harsher stance and sends a strong signal to other EU countries potentially contemplating to leave.

Conclusion

The importance of free trade was not questioned by leading Brexiteers at all. Quite the opposite: it was a major argument of the Leave campaign that Britain would be able to conclude superior trade agreements with other countries thereby counterbalancing some of the impact from exiting the EU single market. Yet this seems unrealistic. Britain will find it difficult to replicate the collective weight representing a unified economic bloc. Also, the sheer number of the EU’s FTAs is difficult to replicate.

With half a billion of the most prosperous people of the world and above €12 trillion in GDP, the EU represents to world’s largest single market, foreign investor and trade partner. Lord Hill, Britain’s former EU commissioner, mentioned at this year’s Königswinter Conference that the EU has more FTAs than any other trading bloc or country in the world, and more than twice as many as the US. These do not include the FTAs currently being negotiated/ratified with the US (TTIP), Canada (CETA), Japan, India, Australia, New Zealand and others.

While Britain might not quite be regarded as an economic light weight, it will struggle to negotiate at eye level with the large trading blocs of this world. Without some flexibility on free movement, Britain faces a humongous task if it tries to emulate the EU’s success in international trade.

On the other hand, losing Britain will weaken the European market distinctly, reduce its size and diversity as well as its competitiveness and growth prospects. There are more than enough incentives for both Britain and the EU to hammer out a workable compromise.

[1] OECD Economic Policy Paper No 16, The Economic Consequences of Brexit: A Taxing Decision, April 2016

[2] HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives, April 2016